Back Xinés antic Catalan Siông-gū Háng-ngṳ̄ CDO Altchinesische Sprache German Malnova ĉina Esperanto Chino antiguo Spanish Antzinako txinera Basque چینی کهن Persian Muinaiskiina Finnish Chinois archaïque French Bahasa Tionghoa Kuno ID

| Old Chinese | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Archaic Chinese | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

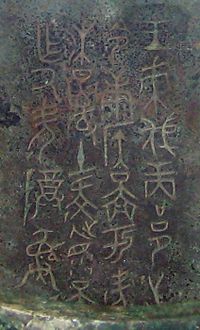

Inscription on the Kang Hou gui (late 11th century BC)[1] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Native to | Ancient China | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Era | Late Shang, Zhou, Warring States period, Qin, Han[a] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Sino-Tibetan

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Language codes | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ISO 639-3 | och | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

och | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Glottolog | shan1294 Shanggu Hanyu | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Linguasphere | 79-AAA-a | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 上古漢語 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 上古汉语 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Old Chinese, also called Archaic Chinese in older works, is the oldest attested stage of Chinese, and the ancestor of all modern varieties of Chinese.[a] The earliest examples of Chinese are divinatory inscriptions on oracle bones from around 1250 BC, in the Late Shang period. Bronze inscriptions became plentiful during the following Zhou dynasty. The latter part of the Zhou period saw a flowering of literature, including classical works such as the Analects, the Mencius, and the Zuo Zhuan. These works served as models for Literary Chinese (or Classical Chinese), which remained the written standard until the early twentieth century, thus preserving the vocabulary and grammar of late Old Chinese.

Old Chinese was written with several early forms of Chinese characters, including oracle bone, bronze, and seal scripts. Throughout the Old Chinese period, there was a close correspondence between a character and a monosyllabic and monomorphemic word. Although the script is not alphabetic, the majority of characters were created based on phonetic considerations. At first, words that were difficult to represent visually were written using a "borrowed" character for a similar-sounding word (rebus principle). Later on, to reduce ambiguity, new characters were created for these phonetic borrowings by appending a radical that conveys a broad semantic category, resulting in compound xingsheng (phono-semantic) characters (形聲字). For the earliest attested stage of Old Chinese of the late Shang dynasty, the phonetic information implicit in these xingsheng characters which are grouped into phonetic series, known as the xiesheng series, represents the only direct source of phonological data for reconstructing the language. The corpus of xingsheng characters was greatly expanded in the following Zhou dynasty. In addition, the rhymes of the earliest recorded poems, primarily those of the Classic of Poetry, provide an extensive source of phonological information with respect to syllable finals for the Central Plains dialects during the Western Zhou and Spring and Autumn periods. Similarly, the Chu Ci provides rhyme data for the dialect spoken in the Chu region during the Warring States period. These rhymes, together with clues from the phonetic components of xingsheng characters, allow most characters attested in Old Chinese to be assigned to one of 30 or 31 rhyme groups. For late Old Chinese of the Han period, the modern Southern Min languages, the oldest layer of Sino-Vietnamese vocabulary, and a few early transliterations of foreign proper names, as well as names for non-native flora and fauna, also provide insights into language reconstruction.

Although many of the finer details remain unclear, most scholars agree that Old Chinese differed from Middle Chinese in lacking retroflex and palatal obstruents but having initial consonant clusters of some sort, and in having voiceless nasals and liquids. Most recent reconstructions also describe Old Chinese as a language without tones, but having consonant clusters at the end of the syllable, which developed into tone distinctions in Middle Chinese.

Most researchers trace the core vocabulary of Old Chinese to Sino-Tibetan, with much early borrowing from neighbouring languages. During the Zhou period, the originally monosyllabic vocabulary was augmented with polysyllabic words formed by compounding and reduplication, although monosyllabic vocabulary was still predominant. Unlike Middle Chinese and the modern Chinese languages, Old Chinese had a significant amount of derivational morphology. Several affixes have been identified, including ones for the verbification of nouns, conversion between transitive and intransitive verbs, and formation of causative verbs.[4] Like modern Chinese, it appears to be uninflected, though a pronoun case and number system seems to have existed during the Shang and early Zhou but was already in the process of disappearing by the Classical period.[5] Likewise, by the Classical period, most morphological derivations had become unproductive or vestigial, and grammatical relationships were primarily indicated using word order and grammatical particles.

- ^ Shaughnessy (1997), p. 61.

- ^ Tai & Chan (1999), pp. 225–233.

- ^ Baxter & Sagart (2014), p. 33.

- ^ Pulleyblank, Edwin G. (2000). "Morphology in Old Chinese". Journal of Chinese Linguistics. 28 (1): 26–51. JSTOR 23754003.

- ^ Wang, Li, 1900–1986.; 王力, 1900–1986 (1980). Han yu shi gao (2010 reprint ed.). Beijing: Zhonghua shu ju. pp. 302–311. ISBN 7101015530. OCLC 17030714.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

Cite error: There are <ref group=lower-alpha> tags or {{efn}} templates on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=lower-alpha}} template or {{notelist}} template (see the help page).