Back Ostsiedlung AN التوسع الألماني الشرقي Arabic Ostsiedlung AST Разселване на немците на изток Bulgarian Ostsiedlung Catalan Německá východní kolonizace Czech Tysk kolonisering i middelalderen Danish Hochmittelalterliche Ostsiedlung German Όστζιντλουνγκ Greek Germana orienta koloniigado Esperanto

| History of Germany |

|---|

|

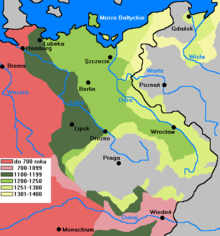

Ostsiedlung (German pronunciation: [ˈɔstˌziːdlʊŋ], lit. 'East settlement') is the term for the Early Medieval and High Medieval migration of ethnic Germans and Germanization of the areas populated by Slavic, Baltic and Uralic peoples; the most settled area was known as Germania Slavica. Germanization efforts included eastern parts of Francia, East Francia, and the Holy Roman Empire and beyond; and the consequences for settlement development and social structures in the areas of settlement. Other regions were also settled, though not as heavily. The Ostsiedlung encompassed multiple modern and historical regions, primarily Germany east of the Saale and Elbe rivers, the states of Lower Austria and Styria in Austria, Poland and the Czech Republic, but also in other parts of Central and Eastern Europe.[1][2]

The majority of Ostsiedlung settlers moved individually, in independent efforts, in multiple stages and on different routes. Many settlers were encouraged and invited by the local princes and regional lords,[3][4][5] who sometimes even expelled part of the indigenous populations to make room for German settlers.[a]

Smaller groups of migrants first moved to the east during the early Middle Ages. Larger treks of settlers, which included scholars, monks, missionaries, craftsmen and artisans, often invited, in numbers unverifiable, first moved eastwards during the mid-12th century. The military territorial conquests and punitive expeditions of the Ottonian and Salian emperors during the 11th and 12th centuries do not form part of the Ostsiedlung, as these actions didn't result in any noteworthy settlement establishment east of the Elbe and Saale rivers. The Ostsiedlung is considered to have been a purely Medieval event as it ended in the beginning of the 14th century. The legal, cultural, linguistic, religious and economic changes caused by the movement had a profound influence on the history of Eastern Central Europe between the Baltic Sea and the Carpathians until the 20th century.[7][8][9]

In the 20th century, accounts of the Ostsiedlung were heavily exploited by German nationalists (including the Nazi movement)[10] to press the territorial claims of Germany and to demonstrate supposed German superiority over non-Germanic peoples, whose cultural, urban and scientific achievements in that era were undermined, rejected, or presented as German.[11][failed verification][12][13] After World War I (1914–1918), the fact that Germany and Austria lost part of their territories in the East appeared as a counterpoint to Ostsiedlung because some of the Germans in the East became foreign citizens when their homes were no longer part of Germany and Austria. The Germans in the East outside Germany and Austria were partially forced to leave and the regions that Germany and Austria lost in the East were dominated by non-German peoples, so the German loss here was not as severe as after World War II.

In and after World War II (1944–1950), Germans were driven out and deported to rump Germany from the East and their language and culture were lost in most areas (including the German-dominated lands which Germany lost after this war) in which German people had settled during the Ostsiedlung; except part of Eastern Austria and especially Eastern Germany.

- ^ Alan V. Murray (15 May 2017). The North-Eastern Frontiers of Medieval Europe: The Expansion of Latin Christendom in the Baltic Lands. Taylor & Francis. pp. 23–. ISBN 978-1-351-88483-9.

- ^ Nora Berend (15 May 2017). The Expansion of Central Europe in the Middle Ages. Taylor & Francis. pp. 194–. ISBN 978-1-351-89008-3.

- ^ Vejas Gabriel Liulevicius (9 December 2010). The German Myth of the East: 1800 to the Present – p. 1. OUP Oxford. ISBN 978-0-19-960516-3.

- ^ Ostsiedlung – ein gesamteuropäisches Phänomen. GRIN Verlag. 25 May 2002. ISBN 978-3-640-04806-9. Retrieved 25 July 2020.

- ^ Szabo 2008, p. 9.

- ^ Palgrave Macmillan UK 1999, p. 11.

- ^ Bartlett 1998, p. 14.

- ^ Szabo 2008, p. 10.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

szewas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ "The Slippery Memory of Men": The Place of Pomerania in the Medieval Kingdom of Poland (East Central and Eastern Europe in the Middle Ages, 450–1450), by Paul Milliman. Brill: Leiden, 2013, page 2 – "There is a huge literature on this topic in Polish and German, which was until recently lumped together with a whole host of other topics (including the peaceful settlement in East Central Europe of Germans and other western Europeans, who had been invited by Slavic lords) as the Drang nach Osten. Because of this term's associations with nineteenth-century nationalism and twentieth-century Nazism, it has for the most part been scrapped, only to be replaced by the deceptively benign 'Ostsiedlung' or the even more problematical 'Ostkolonisation[...]' [...]."

- ^ The Slippery Memory of Men (East Central and Eastern Europe in the Middle Ages, 450–1450) by Paul Milliman page 2.

- ^ Jan M. Piskorski: "The historiography of the so-called 'east colonisation' and the current state of research" in: The Man of Many Devices, Who Wandered Full Many Ways ...: Festschrift in Honor of Janos M.Bak [Hardcover] Balázs Nagy (Editor), Marcell Sebok (Editor) page 654, 655.

- ^ The Holocaust as Colonial Genocide: Hitler's 'Indian Wars' in the 'Wild East' – page 38; Carroll P. Kakel III – 2013: "Within National Socialist discourse, the Nazis purposefully and skillfully presented their eastern colonization project as a 'continuation of medieval Ostkolonisation [eastern colonization], celebrated in the language of continuity, legacy, and colonial grandeur".

Cite error: There are <ref group=lower-alpha> tags or {{efn}} templates on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=lower-alpha}} template or {{notelist}} template (see the help page).