Back Osoonuitputting Afrikaans نضوب الأوزون Arabic Ozon dəliyi Azerbaijani Изтъняване на озоновия слой Bulgarian ओजोन कटाव आ ओजोन छेद Bihari ওজোনস্তর ক্ষয় Bengali/Bangla Ozonska rupa BS Forat de la capa d'ozó Catalan Ozonová díra Czech Озон шăтăкĕ CV

| Part of a series on |

| Pollution |

|---|

|

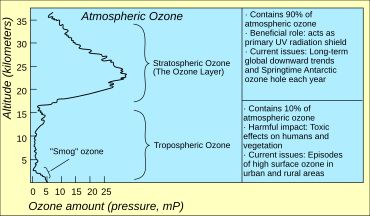

Ozone depletion consists of two related events observed since the late 1970s: a steady lowering of about four percent in the total amount of ozone in Earth's atmosphere,[citation needed] and a much larger springtime decrease in stratospheric ozone (the ozone layer) around Earth's polar regions.[1] The latter phenomenon is referred to as the ozone hole. There are also springtime polar tropospheric ozone depletion events in addition to these stratospheric events.

The main causes of ozone depletion and the ozone hole are manufactured chemicals, especially manufactured halocarbon refrigerants, solvents, propellants, and foam-blowing agents (chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs), HCFCs, halons), referred to as ozone-depleting substances (ODS).[2] These compounds are transported into the stratosphere by turbulent mixing after being emitted from the surface, mixing much faster than the molecules can settle.[3] Once in the stratosphere, they release atoms from the halogen group through photodissociation, which catalyze the breakdown of ozone (O3) into oxygen (O2).[4] Both types of ozone depletion were observed to increase as emissions of halocarbons increased.

Ozone depletion and the ozone hole have generated worldwide concern over increased cancer risks and other negative effects. The ozone layer prevents harmful wavelengths of ultraviolet (UVB) light from passing through the Earth's atmosphere. These wavelengths cause skin cancer, sunburn, permanent blindness, and cataracts,[5] which were projected to increase dramatically as a result of thinning ozone, as well as harming plants and animals. These concerns led to the adoption of the Montreal Protocol in 1987, which bans the production of CFCs, halons, and other ozone-depleting chemicals.[6] Over time, scientists have developed new refrigerants with lower global warming potential (GWP) to replace older ones. For example, in new automobiles, R-1234yf systems are now common, being chosen over refrigerants with much higher GWP such as R-134a and R-12.

The ban came into effect in 1989. Ozone levels stabilized by the mid-1990s and began to recover in the 2000s, as the shifting of the jet stream in the southern hemisphere towards the south pole has stopped and might even be reversing.[7] Recovery was projected to continue over the next century, with the ozone hole expected to reach pre-1980 levels by around 2075.[8] In 2019, NASA reported that the ozone hole was the smallest ever since it was first discovered in 1982.[9][10] The UN now projects that under the current regulations the ozone layer will completely regenerate by 2045.[11][12] The Montreal Protocol is considered the most successful international environmental agreement to date.[13][14]

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

WMO-20Qwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Gruijl, Frank de; Leun, Jan (October 3, 2000). "Environment and health: 3. Ozone depletion and ultraviolet radiation". CMAJ. 163 (7): 851–855. PMC 80511. PMID 11033716 – via www.cmaj.ca.

- ^ Andino, Jean M. (October 21, 1999). "Chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) are heavier than air, so how do scientists suppose that these chemicals reach the altitude of the ozone layer to adversely affect it ?". Scientific American. 264: 68.

- ^ "Part III. The Science of the Ozone Hole". Retrieved March 5, 2007.

- ^ "Ultraviolet (UV) Radiation". www.cancer.org. Retrieved 2022-04-06.

- ^ "The Montreal Protocol on Substances That Deplete the Ozone Layer". United States Department of State. Retrieved 2022-04-06.

- ^ Banerjee, Antara; et al. (2020). "A pause in Southern Hemisphere circulation trends due to the Montreal Protocol". Vol. 579. Nature. pp. 544–548. doi:10.1038/s41586-020-2120-4.

- ^ "The Antarctic Ozone Hole Will Recover". NASA. June 4, 2015. Retrieved 2017-08-05.

- ^ Bowden, John (2019-10-21). "Ozone hole shrinks to lowest size since 1982, unrelated to climate change: NASA". The Hill. Retrieved 2019-10-22.

- ^ Ansari, Talal (October 23, 2019). "Ozone Hole Above Antarctica Shrinks to Smallest Size on Record". The Wall Street Journal – via www.wsj.com.

- ^ "The Week". No. 1418. Future PLC. 14 January 2023. p. 2.

- ^ Laboratory (CSL), NOAA Chemical Sciences. "NOAA CSL: Scientific Assessment of Ozone Depletion: 2022". www.csl.noaa.gov. Retrieved 2024-03-24.

- ^ "The Ozone Hole – The Montreal Protocol on Substances that Deplete the Ozone Layer". Theozonehole.com. 16 September 1987. Archived from the original on 2012-09-12. Retrieved 2019-05-15.

- ^ "Background for International Day for the Preservation of the Ozone Layer – 16 September". www.un.org. Retrieved 2019-05-15.