Back باتشاماما Arabic Pachamama Aymara Pachamama BAR পাচামামা Bengali/Bangla Pacha Mama Catalan Pachamama CDO Pačamama Czech Pachamama Danish Pachamama German Μάμα Πάτσα Greek

| Pachamama | |

|---|---|

Earth, life, harvest, farming, crops, fertility | |

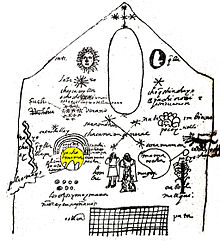

Representation of Pachamama in the cosmology, illustrated by Juan de Santa Cruz Pachacuti Yamqui Salcamaygua (1613), after a picture in the Sun Temple Qurikancha in Cusco | |

| Other names | Mama Pacha, Mother Earth, Queen Pachamama |

| Region | Andes Mountains (Inca Empire) |

| Parents | Viracocha |

| Consort | Pacha Kamaq, Inti |

| Offspring | Inti Mama Killa |

Pachamama is a goddess revered by the indigenous peoples of the Andes. In Inca mythology she is an "Earth Mother" type goddess,[1] and a fertility goddess who presides over planting and harvesting, embodies the mountains, and causes earthquakes. She is also an ever-present and independent deity who has her own creative power to sustain life on Earth.[1] Her shrines are hallowed rocks, or the boles of legendary trees, and her artists envision her as an adult female bearing harvests of potatoes or coca leaves.[2] The four cosmological Quechua principles – Water, Earth, Sun, and Moon[2] – claim Pachamama as their prime origin. Priests sacrifice offerings of llamas, cuy (guinea pigs), and elaborate, miniature, burned garments to her.[3] Pachamama is the mother of Inti the sun god, and Mama Killa the moon goddess. Mama Killa is said to be the wife of Inti.

After the Spanish colonization of the Americas, they converted the native populations of the region to Roman Catholicism. Due to religious syncretism, the figure of the Virgin Mary was associated with that of the Pachamama for many of the indigenous people.[4]

As Andean cultures formed modern nations, the figure of Pachamama was still believed to be benevolent, generous with her gifts,[5] and a local name for Mother Nature. In the 21st century, many indigenous peoples in South America base environmental concerns in these ancient beliefs, saying that problems arise when people take too much from nature because they are taking too much from Pachamama.[6]

- ^ a b Dransart, Penny. (1992) "Pachamama: The Inka Earth Mother of the Long Sweeping Garment." Dress and Gender: Making and Meaning. Ed. Ruth Barnes and Joanne B. Eicher. New York/Oxford: Berg. 145-63. Print.

- ^ a b Cite error: The named reference

MatthewsSalazar71-81was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Murra, John V. (1962). "Cloth and Its Functions in the Inca State". American Anthropologist. 64 (4): 714. doi:10.1525/aa.1962.64.4.02a00020.

- ^ Merlino, Rodolfo y Mario Rabey (1992). "Resistencia y hegemonía: Cultos locales y religión centralizada en los Andes del Sur". Allpanchis (in Spanish) (40): 173–200. doi:10.36901/allpanchis.v24i40.799.

- ^ Molinie, Antoinette (2004). "The Resurrection of the Inca: The Role of Indian Representations in the Invention of the Peruvian Nation". History and Anthropology. 15 (3): 233–250. doi:10.1080/0275720042000257467. S2CID 162202435.

- ^ Hill, Michael (2008). "Inca of the Blood, Inca of the Soul". Journal of the American Academy of Religion. 76 (2): 251–279. doi:10.1093/jaarel/lfn007. PMID 20681090. S2CID 20198583.