Back تقسيم الدولة العثمانية Arabic Osmanlı imperiyasının bölünməsi Azerbaijani Partició de l'Imperi Otomà Catalan Διαμελισμός της Οθωμανικής Αυτοκρατορίας Greek Partición del Imperio otomano Spanish تجزیه امپراتوری عثمانی Persian Partition de l'Empire ottoman French חלוקת האימפריה העות'מאנית HE Օսմանյան կայսրության բաժանում Armenian Pemisahan Kekaisaran Utsmaniyah ID

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (May 2018) |

| History of the Ottoman Empire |

|---|

|

| Timeline |

| Historiography (Ghaza, Decline) |

| Paris Peace Conference |

|---|

|

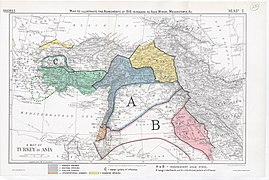

The partition of the Ottoman Empire (30 October 1918 – 1 November 1922) was a geopolitical event that occurred after World War I and the occupation of Constantinople by British, French, and Italian troops in November 1918. The partitioning was planned in several agreements made by the Allied Powers early in the course of World War I,[1] notably the Sykes–Picot Agreement, after the Ottoman Empire had joined Germany to form the Ottoman–German alliance.[2] The huge conglomeration of territories and peoples that formerly comprised the Ottoman Empire was divided into several new states.[3] The Ottoman Empire had been the leading Islamic state in geopolitical, cultural, and ideological terms. The partitioning of the Ottoman Empire after the war led to the domination of the Middle East by Western powers such as Britain and France, and saw the creation of the modern Arab world and the Republic of Turkey. Resistance to the influence of these powers came from the Turkish National Movement but did not become widespread in the other post-Ottoman states until the period of rapid decolonization after World War II.

The sometimes-violent creation of protectorates in Iraq and Palestine, and the proposed division of Syria along communal lines, is thought to have been a part of the larger strategy of ensuring tension in the Middle East, thus necessitating the role of Western colonial powers (at that time Britain, France and Italy) as peace brokers and arms suppliers.[4] The League of Nations mandate granted the French Mandate for Syria and the Lebanon, the British Mandate for Mesopotamia (later Iraq) and the British Mandate for Palestine, later divided into Mandatory Palestine and the Emirate of Transjordan (1921–1946). The Ottoman Empire's possessions in the Arabian Peninsula became the Kingdom of Hejaz, which the Sultanate of Nejd (today Saudi Arabia) was allowed to annex, and the Mutawakkilite Kingdom of Yemen. The Empire's possessions on the western shores of the Persian Gulf were variously annexed by Saudi Arabia (al-Ahsa and Qatif), or remained British protectorates (Kuwait, Bahrain, and Qatar) and became the Arab States of the Persian Gulf.

After the Ottoman government collapsed completely, its representatives signed the Treaty of Sèvres in 1920, which would have partitioned much of the territory of present-day Turkey among France, the United Kingdom, Greece and Italy. The Turkish War of Independence forced the Western European powers to return to the negotiating table before the treaty could be ratified. The Western Europeans and the Grand National Assembly of Turkey signed and ratified the new Treaty of Lausanne in 1923, superseding the Treaty of Sèvres and agreeing on most of the territorial issues.[5]

One unresolved issue, the dispute between the Kingdom of Iraq and the Republic of Turkey over the former province of Mosul, was later negotiated under the auspices of the League of Nations in 1926. The British and French partitioned the region of Syria between them in the Sykes-Picot Agreement. Other secret agreements were concluded with Italy and Russia.[6] The international Zionist movement, after their successful lobbying for the Balfour Declaration, encouraged the push for a Jewish homeland in Palestine. While a part of the Triple Entente, Russia also had wartime agreements preventing it from participating in the partitioning of the Ottoman Empire after the Russian Revolution. The Treaty of Sèvres formally acknowledged the new League of Nations mandates in the region, the independence of Yemen, and British sovereignty over Cyprus.

- ^ Paul C. Helmreich, From Paris to Sèvres: The Partition of the Ottoman Empire at the Peace Conference of 1919–1920 (Ohio University Press, 1974) ISBN 0-8142-0170-9

- ^ Fromkin, A Peace to End All Peace (1989), pp. 49–50.

- ^ Roderic H. Davison; Review "From Paris to Sèvres: The Partition of the Ottoman Empire at the Peace Conference of 1919–1920" by Paul C. Helmreich in Slavic Review, Vol. 34, No. 1 (Mar. 1975), pp. 186–187

- ^ Baer, Robert. See No Evil: The True Story of a Ground Soldier in the CIA's War on Terrorism. Broadway Books.[page needed]

- ^ P. Helmreich, From Paris to Sèvres (Ohio State University Press, 1974)

- ^ P. Helmreich, From Paris to Sèvres (Ohio State University Press, 1974)