Back Fisionomie Afrikaans علم الفراسة Arabic Fisiognomia Catalan زانستی فیراسە CKB Fyziognomie Czech Fysiognomik Danish Physiognomik German Fiziognomiko Esperanto Fisiognomía Spanish Fisiognomia Basque

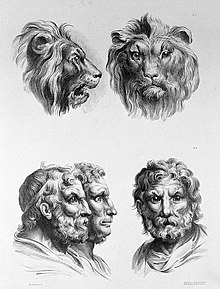

Physiognomy (from the Greek φύσις, ['physis'] Error: {{Transliteration}}: transliteration text not Latin script (help), meaning "nature", and ['gnomon'] Error: {{Transliteration}}: transliteration text not Latin script (help), meaning "judge" or "interpreter") or face reading is the practice of assessing a person's character or personality from their outer appearance—especially the face. The term can also refer to the general appearance of a person, object, or terrain without reference to its implied characteristics—as in the physiognomy of an individual plant (see plant life-form) or of a plant community (see vegetation).

Physiognomy as a practice meets the contemporary definition of pseudoscience[1][2][3] and is regarded as such by academics because of its unsupported claims; popular belief in the practice of physiognomy is nonetheless still widespread and modern advances in artificial intelligence have sparked renewed interest in the field of study. The practice was well-accepted by ancient Greek philosophers, but fell into disrepute in the 16th century while practised by vagabonds and mountebanks. It revived and was popularised by Johann Kaspar Lavater, before falling from favour in the late 19th century.[4] Physiognomy in the 19th century is particularly noted as a basis for scientific racism.[5] Physiognomy as it is understood today is a subject of renewed scientific interest, especially as it relates to machine learning and facial recognition technology.[6][7][8] The main interest for scientists today are the risks, including privacy concerns, of physiognomy in the context of facial recognition algorithms.

Physiognomy is sometimes referred to as anthroposcopy, a term originating in the 19th century.[9]

- ^ Roy Porter (2003). "Marginalized practices". The Cambridge History of Science: Eighteenth-century science. Vol. 4 (illustrated ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 495–497. ISBN 978-0-521-57243-9.

Although we bracket physiognomy with Mesmerism as discredited or laughable belief, many eighteenth-century writers referred to it as a useful science with a long history ... Although many modern historians belittle physiognomy as a pseudoscience, at the end of the eighteenth century, it was not merely a popular fad, but also the subject of intense academic debate about the promises it held for progress.

- ^ "physiognomy". The Skeptic's Dictionary. 2013.

- ^ Jaeger, Bastian (June 26, 2020). "Lay beliefs in physiognomy explain overreliance on facial impressions". PsyArXiv.

- ^ Wiseman, Richard; Highfield, Roger; Jenkins, Rob (11 February 2009). "How your looks betray your personality". New Scientist.

- ^ American Anthropological Association. "Eugenics and Physical Anthropology". August 7, 2007.[verification needed]

- ^ Wang, Yilun; Kosinski, Michal (February 2018). "Deep neural networks are more accurate than humans at detecting sexual orientation from facial images". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 114 (2): 246–257. doi:10.1037/pspa0000098. PMID 29389215. S2CID 1379347.

- ^ Johns, David Merritt (14 October 2009). "Facial Profiling". Slate.

- ^ Kosinski, Michal (11 January 2021). "Facial recognition technology can expose political orientation from naturalistic facial images". Scientific Reports. 11 (1): 100. Bibcode:2021NatSR..11..100K. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-79310-1. PMC 7801376. PMID 33431957. S2CID 231583415.

- ^ "Anthroposcopy - Define Anthroposcopy at Dictionary.com". Dictionary.com.