Back بوابة:بولندا/مقالة مختارة Arabic Πύλη:Πολωνία/Επιλεγμένο λήμμα Greek Portal:Polonia/Seleccionado Spanish Portal:Polska/Artykuł na medal Polish Portal:Polonia/Articol selectat Romanian Портал:Польша/Примечательная статья Russian Портал:Пољска/Изабрани Serbian Портал:Польща/Вибрана стаття Ukrainian

These are excerpts from articles about the History of Poland that appear on the Poland Portal. See talk page for instructions about adding new articles.

Selected article 1

Portal:Poland/Selected article/1

The history of Solidarity, a Polish non-governmental trade union, began in August 1980 at the Lenin Shipyard in Gdańsk where it was started by Lech Wałęsa and his co-workers. In the early 1980s, it became the first independent labor union in a Soviet-bloc country. Solidarity gave rise to a broad anti-communist nonviolent social movement that, at its height, united some 10 million members and vastly contributed to the fall of communism. Poland's communist government attempted to destroy it by imposing martial law in 1981, followed by several years of political repression, but it was ultimately forced to begin negotiating with the union. Round Table Talks between the weakened government and the Solidarity-led opposition resulted in a semi-free parliamentary election in 1989. By the end of August 1989, a Solidarity-led coalition government had been formed and, in December 1990, Wałęsa was elected president. This was soon followed by the dismantling of the communist governmental system and by Poland's transformation into a modern democratic state. Solidarity's example led to the spread of anti-communist ideas and movements throughout the countries of the Eastern Bloc, weakening their communist governments; a process known as the Revolutions of 1989, or the Autumn of Nations. (Full article...)Selected article 2

Portal:Poland/Selected article/2

Selected article 3

Portal:Poland/Selected article/3

The Polish September Campaign was the conquest of Poland by the armies of Nazi Germany, the Soviet Union and a small contingent of Slovak forces during World War II. The campaign began on 1 September 1939 following a German-staged attack in Gleiwitz (Gliwice). This military operation, which saw the first use of Blitzkrieg tactics, marked the start of World War II in Europe as the invasion led Poland's allies, including the United Kingdom and France, to declare war on Germany on 3 September. On 17 September, the Soviet Red Army invaded the eastern regions of Poland. The Soviets were acting in coöperation with Germany, realizing the secret protocol of the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact which envisaged division of Central Europe into Nazi and Soviet spheres of influence. The campaign ended on 6 October 1939 with Germany and the Soviet Union occupying the entirety of Poland. (Full article...)Selected article 4

Portal:Poland/Selected article/4

The Katyn massacre was a mass execution of Polish citizens by the order of Soviet authorities in 1940. About 8,000 of those killed were reserve officers taken prisoner during the 1939 Soviet invasion of Poland, but the dead also included many civilians who had been arrested for being "intelligence agents and gendarmes, spies and saboteurs, former landowners, factory owners and officials". Since Poland's conscription system required every unexempted university graduate to become a reserve officer, the Soviets were thus able to round up much of the ethnic Polish, Jewish, Ukrainian, Georgian and Belarusian intelligentsia of Polish citizenship. The 1943 discovery of mass graves at Katyn Forest by Nazi German forces precipitated a rupture of diplomatic relations between the Soviet Union and the Polish government-in-exile in London. The Soviet Union continued to deny responsibility for the massacres until 1990. Although the Russian government acknowledged that the NKVD had in fact committed the massacres, it does not consider them a war crime or an act of genocide, as this would have necessitated the prosecution of surviving perpetrators. (Full article...)Selected article 5

Portal:Poland/Selected article/5

Selected article 6

Portal:Poland/Selected article/6

The Polish–Soviet War, fought between 1919 and 1921, determined the borders between two nascent states in post–World War I Europe. It was a result of conflicting attempts — by Poland, whose statehood had just been reëstablished after it being partitioned in the late 18th century, to secure territories which it had lost in the partitions — and by the Bolsheviks who aimed to take control of the same territories that had since then been part of Imperial Russia until their occupation by Germany during World War I. The conflict ended with the Peace of Riga which divided Ukraine and Belarus between the Second Polish Republic and the newly formed Soviet Union. Both states claimed victory in the war: the Poles claimed a successful defense of their state, while the Soviets claimed a repulse of the Polish Kiev Offensive, which was sometimes viewed as part of foreign interventions in the Russian Civil War. (Full article...)Selected article 7

Portal:Poland/Selected article/7

The Stone Age in what is now Poland lasted about 500,000 years and involved three different human species: Homo erectus, Homo neanderthalensis and Homo sapiens. Stone Age cultures ranged from early human groups with primitive tools to advanced agricultural societies, which used sophisticated stone tools, built fortified settlements and developed copper metallurgy. As elsewhere in Europe, the Stone Age human cultures went through the stages known as the Paleolithic, Mesolithic and Neolithic, each bringing new refinements of the stone tool making techniques. The Paleolithic human activities were intermittent because of the recurring periods of glaciation. A general climate warming and the resulting increase in ecologic diversity was characteristic of the Mesolithic (9,000-8,000 BCE). The Neolithic brought the first settled agricultural communities whose founders migrated from the Danube River area starting ca. 5,500 BCE. Later the native post-Mesolithic populations also adopted and further developed the agricultural way of life (4,400–2,000 BCE). (Full article...)Selected article 8

Portal:Poland/Selected article/8

Selected article 9

Portal:Poland/Selected article/9

The Warsaw Uprising of 1794 was an armed Polish insurrection by the Warsaw's populace early in the Kościuszko Uprising. Supported by the Polish Army, it aimed to throw off Russian control of the Polish capital. It began on 17 April 1794, soon after Tadeusz Kościuszko's victory at Racławice. A National Militia led by shoemaker Jan Kiliński, armed with rifles and sabers from the Warsaw Arsenal, inflicted heavy losses on the more numerous and better equipped, but surprised enemy garrison. Apart from the militia, the most famous units to take part in the liberation of Warsaw were formed of Poles who had been conscripted into the Russian service. Within hours, the fighting had spread from a single street on the western outskirts of Warsaw's Old Town to the entire city. Part of the Russian garrison was able to retreat under the cover of Prussian cavalry, but most were trapped inside the city. Isolated Russian forces resisted in several areas for two more days. (Full article...)Selected article 10

Portal:Poland/Selected article/10

The Soviet invasion of Poland was a military operation that started without a formal declaration of war on 17 September 1939, during the early stages of World War II, sixteen days after the beginning of the Nazi German attack on Poland. It ended in a decisive victory for the Soviet Union's Red Army. The Soviets acted on the basis of their alliance with Nazi Germany; on 1 September, the Germans invaded Poland from the west and, on 17 September, the Soviet Army invaded from the east. The Red Army quickly achieved its targets, vastly outnumbering Polish resistance, already reeling from the German blows. The Soviet government annexed half of the Polish territory now under its control and in November declared that the 13.5 million Polish citizens who lived there were now Soviet citizens. The Soviets quelled opposition by arrests, deportations and executions. (Full article...)Selected article 11

Portal:Poland/Selected article/11

The Home Army (Armia Krajowa) was the dominant Polish resistance movement in World War II German-occupied Poland. It was loyal to the Polish government-in-exile and constituted the armed wing of what became known as the Polish Underground State. Most common estimates of its membership in 1944 are around 400,000; that figure would make it not only the largest Polish underground resistance movement but one of the two largest in Europe during World War II. The AK's primary resistance operations were the sabotage of German activities; it also fought several full-scale battles against the Germans, particularly in 1943 and 1944 during Operation Tempest. The most widely known AK operation was the failed Warsaw Uprising. (Full article...)Selected article 12

Portal:Poland/Selected article/12

The Smolensk War was a conflict fought between the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth and the Tsardom of Russia over the border city of Smolensk (now in Russia). Following King Sigismund III's death in 1632, Russia invaded Poland with the aim of liberating the city it had lost during the Time of Troubles 14 years earlier. Initially, small military engagements produced mixed results for both sides. A year-long siege with heavy artillery laid to Smolensk by Mikhail Shein was broken by Polish relief forces, including the Winged Hussars, led by Hetman Krzysztof Radziwiłł in 1633. The war ended with the Treaty of Polyanovka in 1634 which left Smolensk in Polish hands for the next 20 years. By the terms of the treaty, Russia paid Poland 20,000 rubles in gold as war indemnity, but Polish King Vladislaus IV had to renounce his claim to the Russian throne. Shein, the hapless Russian commander, was executed for treason. (Full article...)Selected article 13

Portal:Poland/Selected article/13

Selected article 14

Portal:Poland/Selected article/14

The main event that took place within the lands of Poland in the Early Middle Ages was the arrival and permanent settlement of the Slavic peoples. The Slavic migrations in the area of contemporary Poland started in the second half of the 5th century CE, some half century after these territories were vacated by Germanic tribes, their previous inhabitants. The Slavs lived from cultivation of crops, but also engaged in hunting and gathering. They formed small tribal organizations, some of which coalesced later into larger, state-like ones. Beginning in the 7th century, these tribal units built fortified structures with earth and wood walls and embankments, called gords. By the 9th century, the Slavs had settled the Baltic coast in Pomerania, which subsequently developed into a commercial and military power trading with the Old Prussians and the Vikings. During the same time, the tribe of the Vistulans, based in Kraków and the surrounding region, controlled a large area in the south. But it was the Polans who turned out to be of decisive historic importance. They went through a period of accelerated building of fortified settlements and territorial expansion beginning in the first half of the 10th century. Under Mieszko I, the expanded Polan territory was converted to Latin Christianity in 966, which is commonly regarded the birth of the Polish state. (Full article...)Selected article 15

Portal:Poland/Selected article/15

Polish citizens have the world's highest count of individuals awarded medals of "Righteous among the Nations", given by the State of Israel to Gentiles who saved Jews from extermination during the Holocaust. There are 7,232 (as of 1 January 2022[update]) Polish men and women recognized as "Righteous", amounting to over 25 per cent of the total number of 28,217 honorary titles awarded already. It is estimated that in fact hundreds of thousands of Poles concealed and aided hundreds of thousands of their Polish-Jewish neighbors. Many of these initiatives were carried out by individuals, but there also existed organized networks dedicated to aiding Jews—most notably, the Żegota organization. In German-occupied Poland the task of rescuing Jews was especially difficult and dangerous. All household members were punished by death if a Jew was found concealed in their home or on their property. Estimates of the number of Poles who were killed by the Nazis for aiding Jews, among them 704 posthumously honored with medals, go as high as tens of thousands. Notable individuals among the Polish Righteous include Władysław Bartoszewski, Tadeusz Pankiewicz, Irena Sendlerowa and Maria Kotarba. (Full article...)Selected article 16

Portal:Poland/Selected article/16

Selected article 17

Portal:Poland/Selected article/17

The deaths of Joseph Stalin in 1953 and Poland's hardline communist President Bolesław Bierut in 1956, as well as Nikita Khrushchev's secret speech to the 20th Party Congress, paved the way to a period of de-Stalinization in the People's Republic of Poland, known as the Polish October or Gomułka Thaw. Workers' protests against poor standards of living that started in June 1956 in Poznań were violently suppressed by the army and secret police, but forced the government to increase wages and promise economic and political reforms. Władysław Gomułka, who had been expelled from the Polish United Workers' Party and imprisoned in 1951, was rehabilitated and elected the party's First Secretary in October 1956. With much popular support, he led the country along a "Polish road to socialism" and won a degree of autonomy from the Soviet Union. Soviet Marshal Konstantin Rokossovsky was sacked from his post as Polish defense minister, farm collecitivization was halted, Cardinal Stefan Wyszyński was released from internment, and the following year's parliamentary election, though not entirely free, was freer than previous ones. These events inspired the Hungarian Revolution of 1956, which – unlike the one in Poland – was crushed by the Soviet Army. (Full article...)Selected article 18

Portal:Poland/Selected article/18

Operation Tractable was the final Canadian–Polish offensive to take place during the Battle of Normandy. Its aim was to capture the strategically important town of Falaise and subsequently the towns of Trun and Chambois. The operation was undertaken against Germany's Army Group B, and was part of the largest encirclement on the Western Front during World War II. Despite a slow start to the offensive, marked by limited gains north of Falaise, innovative tactics by Gen. Stanisław Maczek's Polish First Armoured Division during the drive for Chambois allowed for the Falaise Gap to be partly closed by August 19, 1944, trapping close to 300,000 German soldiers in the Falaise Pocket. Although the gap had been narrowed to a distance of several hundred meters, a protracted series of fierce engagements between two battlegroups of the 1st Armoured Division and the Second SS Panzer Corps on Mont Ormel prevented it from being completely closed. During two days of nearly continuous fighting, Polish forces, using artillery barrages and close-quarter fighting, managed to hold off counterattacks by elements of seven German divisions. On August 21, elements of the First Canadian Army relieved Polish survivors of the battle and were able to finally close the Falaise Pocket, leading to the capture of the remaining soldiers of the German Seventh Army. (Full article...)Selected article 19

Portal:Poland/Selected article/19

Peoples belonging to numerous archaeological cultures identified with Celtic, Germanic and Baltic tribes, lived in various parts of what is now Poland in Antiquity – an era that dates from about 400 BC to AD 450–500. Many of them developed relatively advanced material culture and social organization, as evidenced by the archaeological record, such as the richly furnished dynastic princely graves. Some preserved written remarks by Roman authors that are relevant to the developments on Polish lands provide additional insight. Celtic peoples established a number of settlement centers, beginning in the early 4th century BC, mostly in southern Poland, which was at the outer edge of their expansion. Through their highly developed economy and crafts, they exerted lasting cultural influence (La Tène culture) disproportional to their small numbers in the region. Germanic peoples lived in today's Poland for several centuries (Wielbark culture). With the expansion of the Roman Empire, the Germanic tribes came under Roman cultural influence. As nomadic peoples invaded from the east, the Germanic people left for the safer and wealthier lands in southern and western Europe. The northeast corner of contemporary Poland's territory remained populated by Baltic tribes. (Full article...)Selected article 20

Portal:Poland/Selected article/20

Polish culture during World War II was brutally suppressed by the occupying powers of Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union, both of whom were hostile to Poland's people and culture. Policies aimed at cultural genocide resulted in the deaths of thousands of scholars and artists, and the theft or destruction of innumerable cultural artifacts (example of a lost painting, by Raphael, pictured). British historian Niall Ferguson writes that "the maltreatment of the Poles was one of many ways in which the Nazi and Soviet regimes had grown to resemble one another". The occupiers looted or destroyed much of Poland's cultural heritage while persecuting and killing members of the Polish cultural elite. Most Polish schools were closed and those that remained open saw their curricula altered significantly. Nevertheless, underground organizations and individuals—in particular the Polish Underground State—saved much of Poland's most valuable cultural heritage and worked to salvage as many cultural institutions and artifacts as possible. The Roman Catholic Church and wealthy individuals contributed to the survival of some artists and their works. Despite severe retribution by the Nazis and Soviets, Polish underground cultural activities, including publications, concerts, live theater, education and academic research, continued throughout the war. (Full article...)Selected article 21

Portal:Poland/Selected article/21

Selected article 22

Portal:Poland/Selected article/22

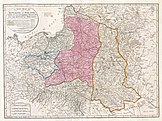

The First Partition of Poland took place in 1772 as the first of three partitions that ended the existence of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth by 1795. Growth in the Russian Empire's power, threatening the Kingdom of Prussia and the Habsburg Austrian Empire, was the primary motive behind this first partition. The weakened Commonwealth's land, including that already controlled by Russia, was apportioned among its more powerful neighbors—Austria, Russia and Prussia—so as to restore the regional balance of power in Eastern Europe among those three countries. With Poland unable to effectively defend itself and with foreign troops already inside the country, the Polish parliament ratified the partition in 1773 during the Partition Sejm convened by the three powers. (Full article...)Selected article 23

Portal:Poland/Selected article/23

Szczerbiec is the coronation sword that was used in crowning ceremonies of most kings of Poland from 1320 to 1764. It is currently on display in the treasure vault of the Royal Wawel Castle in Kraków as the only preserved piece of the Polish crown jewels. The sword is characterized by a hilt decorated with magic formulas, Christian symbols and floral patterns, as well as a narrow slit in the blade which holds a small shield with the coat of arms of Poland. Its name derives from the Polish word szczerba meaning a gap, notch or chip. A legend links Szczerbiec with King Boleslaus the Brave who was said to have chipped the sword by hitting it against the Golden Gate of Kiev during his capture of the city in 1018. However, the sword is actually dated to the late 12th or 13th century, and was first used as a coronation sword by Vladislaus the Elbow-High in 1320. Looted by Prussian troops in 1795, it changed hands several times during the 19th century until it was purchased in 1884 for the Hermitage Museum in Saint Petersburg, Russia. The Soviet Union returned it to Poland in 1928. During World War II, Szczerbiec was evacuated to Canada and did not return to Kraków until 1959. In the 20th century, an image of the sword was adopted as a symbol by Polish nationalist and far-right movements. (Full article...)Selected article 24

Portal:Poland/Selected article/24

The Cipher Bureau (Biuro Szyfrów) was the interwar Polish General Staff's agency charged with both cryptography (the use of ciphers and codes) and cryptology (the study of ciphers and codes, particularly for the purpose of "breaking" them). It was formed in 1931 by the merger of pre-existing agencies. In December 1932, the Bureau began breaking Germany's Enigma ciphers. Over the next seven years, Polish cryptologists overcame the growing structural and operating complexities of the plugboard-equipped Enigma. The Bureau also broke Soviet cryptography. Five weeks before the outbreak of World War II, on 25 July 1939, in Warsaw, the Polish Cipher Bureau revealed its Enigma-decryption techniques and equipment (example pictured) to representatives of French and British military intelligence, which had been unable to make any headway against Enigma. This Polish intelligence and technology transfer would give the Allies an unprecedented advantage (see Ultra) in their ultimately victorious prosecution of the war. (Full article...)Selected article 25

Portal:Poland/Selected article/25

The Battle of Grunwald, fought on 15 July 1410, was one of the largest battles of Medieval Europe and is regarded as the most important victory in the history of Poland and Lithuania. The alliance of the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, led respectively by King Vladislaus II (Jogaila, Jagiełło) and Grand Duke Vytautas, decisively defeated the Teutonic Knights, led by Grand Master Ulrich von Jungingen. Although the defeated Teutonic Knights withstood the siege on their fortress in Marienburg (Malbork) and suffered only minimal territorial losses at the Peace of Thorn (Toruń), they never recovered their former power, and the financial burden of war reparations caused internal conflicts and an economic downturn in their lands. The battle shifted the balance of power in Eastern Europe and marked the rise of the Polish–Lithuanian union as the dominant political and military force in the region. Surrounded by romantic legends and nationalist propaganda, Grunwald became a symbol of struggle against invaders and a source of national pride, also used in Nazi and Soviet propaganda campaigns. Only in recent decades have historians made progress towards a dispassionate, scholarly assessment of the battle reconciling the previous narratives, which differed widely by nation. (Full article...)Selected article 26

Portal:Poland/Selected article/26

The rule of the Piast dynasty was the first major stage in the history of Poland. The indigenous House of Piast was largely responsible for the formation of the Polish state in the 10th century and ruled until the second half of the 14th century. Mieszko I completed the unification of West Slavic tribal lands and chose to be baptized in the Latin Church in 966. His son, Boleslaus the Brave, pursued territorial conquests and was crowned as the first king of Poland. Boleslaus the Bold brought back Poland's military assertiveness, but was expelled from the country due to a conflict with Bishop Stanislaus of Szczepanów. Boleslaus Wrymouth succeeded in defending his country and recovering territories previously lost, but upon his death in 1138, Poland was divided among his sons. The resulting internal fragmentation eroded the initial Piast monarchy structure in the 12th and 13th centuries, causing fundamental and lasting changes. The kingdom was restored under Vladislaus the Elbow-high, then strengthened and expanded by his son, Casimir the Great. The consolidation in the 14th century laid the base for the new powerful Kingdom of Poland that was to follow. (Full article...)Selected article 27

Portal:Poland/Selected article/27

Selected article 28

Portal:Poland/Selected article/28

The history of Poland during the Jagiellon dynasty spanned the late Middle Ages and Early Modern Era. Beginning with Grand Duke Jogaila of Lithuania, the House of Jagiellon formed the Polish-Lithuanian dynastic union. The partnership brought vast Lithuanian-controlled Rus' areas into Poland's sphere of influence and proved beneficial for the Poles and the Lithuanians, who coöperated in one of Europe's largest political entities for the next four centuries. In the Baltic Sea region, Poland's struggle with the Teutonic Knights included the Battle of Grunwald, and the milestone Peace of Thorn under King Casimir IV. In the south, Poland confronted the Ottoman Empire and the Crimean Tatars, while in the east, it helped Lithuania fight the Grand Duchy of Moscow. Poland was developing as a feudal state, with predominantly agricultural economy and an increasingly dominant landed nobility component. The Nihil novi act adopted in 1505, transferred most of the legislative power from the monarch to the Sejm (parliament), beginning a period of "Golden Liberty", when the state was ruled by the "free and equal" Polish nobility. Protestant Reformation resulted in policies of religious toleration that were unique in Europe at that time, while Renaissance currents evoked an immense cultural flowering under kings Sigismund I and Sigismund Augustus. (Full article...)Selected article 29

Portal:Poland/Selected article/29

The history of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth from 1569 to 1648 covers a period of Poland's rise and expansion, before it was subjected to devastating wars in the middle of the 17th century. The Union of Lublin of 1569 established the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, a federal state replacing the previous dynastic union of the two nations. The Commonwealth was run by the nobility, through a system of a central parliament and local assemblies, under elected kings. It was a period of Poland's great power, civilizational advancement and prosperity. The Commonwealth had become an influential player in Europe, spreading the Western culture eastward. The Warsaw Confederation of 1573 was the culmination of religious toleration that was unique in Europe, but the Catholic Church soon embarked on an ideological counter-offensive, while the Union of Brest split the Eastern Christians within the Commonwealth. The Commonwealth fought mostly successful wars with Russia, Sweden and the Ottoman Empire, but it gradually became a playground of internal conflicts, in which kings, powerful magnates and factions of nobility were the main actors. (Full article...)Selected article 30

Portal:Poland/Selected article/30

The Łódź Insurrection was an uprising by Polish workers in Łódź against the Russian Empire which took place between 21 and 25 June 1905. The Russian-controlled Congress Poland was one of the major centers of the Russian Revolution of 1905, and the Łódź Insurrection was a key incident in those events. For months prior to the uprising, workers in Łódź had been in a state of unrest, with several major strikes brutally quelled by the Russian police and military. Around 21–22 June, angry workers began building barricades and assaulting police and military patrols. The riots began spontaneously, without backing from any organized group; Polish revolutionary groups were taken by surprise and did not play a major role in the subsequent events. Authorities declared martial law and called in additional troops. No businesses operated in the city on 23 June as the police and military stormed dozens of workers' barricades. Eventually, by 25 June, the uprising was crushed, with estimates of several hundred dead and wounded. The events were reported in international press and recognized by socialist and communist activists worldwide. (Full article...)Selected article 31

Portal:Poland/Selected article/31

Constitution of 3 May 1791 is a large Romantic oil painting by Jan Matejko. It was painted in 1891 to commemorate the centenary of the Polish Constitution of 1791, a milestone in the history of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth and the high point of the Polish Enlightenment. Set in the late afternoon of 3 May 1791, the canvas shows a procession from Warsaw's Royal Castle, where the Constitution has just been adopted by the Great Sejm, to St. John's Collegiate Church. While the procession was a historical event, Matejko took many artistic liberties, such as including persons who were not in fact present or had died earlier, because he intended the painting to be a synthesis of the final years of the Commonwealth. Like many works by the same artist, the picture presents a grand scene populated with numerous historic figures, including King Stanislaus Augustus; Marshals of the Great Sejm, Stanisław Małachowski and Kazimierz Nestor Sapieha; and co-authors of the Constitution such as Hugo Kołłątaj and Ignacy Potocki. Altogether, some twenty individuals have been identified by modern historians. Originally displayed in Lviv, the work now hangs at the Royal Castle of Warsaw. (Full article...)Selected article 32

Portal:Poland/Selected article/32

The Polish Constitution of 1791, the world's second oldest written constitution after that of the United States, was adopted by the Great Sejm on 3 May 1791. The document was designed to redress political defects of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, such as the system of "Golden Liberty", which had corrupted the country's politics. It sought to supplant the prevailing anarchy, fostered by some of the country's magnates, with a more democratic constitutional monarchy. It introduced elements of political equality between townspeople and nobility, and placed the peasants under the protection of the government, thus mitigating the worst abuses of serfdom. It also banned pernicious parliamentary institutions such as the liberum veto, which allowed any single deputy to undo all the legislation that had been passed during a given session of the Sejm. The constitution remained in force for less than 15 months and was abolished following the Constitution War against Russia and the Russian-supported Targowica Confederation, a coalition of Polish magnates and landless nobility who opposed reforms that might have weakened their influence. In the words of two of the document's co-authors, Ignacy Potocki and Hugo Kołłątaj, it was "the last will and testament of the expiring Country." (Full article...)Selected article 33

Portal:Poland/Selected article/33

The Polish Legions were Polish military units that served with the French Army, mainly from 1797 to 1803, although some units continued to serve until 1815. The legionaries were recruited from among soldiers, officers and volunteers who had emigrated to Italy and France after the Third Partition of Poland in 1795. Many Poles at that time believed that Revolutionary France and her allies would come to Poland's aid, as France's enemies included Poland's partitioners: Prussia, Austria and Russia. With Napoleon Bonaparte's support, Polish military units were formed, bearing Polish military ranks and commanded by Polish officers, such as Jan Henryk Dąbrowski, Karol Kniaziewicz, and Józef Wybicki. Serving alongside the French Army, Polish Legions saw combat in most of Napoleon's campaigns, from the West Indies, to Italy, to Egypt. When the Duchy of Warsaw was created in 1807, many veterans of the Legions formed a core around which the Duchy's army was raised under Prince Józef Poniatowski, which went on to fight alongside the French army in several campaigns, culminating in the disastrous invasion of Russia in 1812. (Full article...)Selected article 34

Portal:Poland/Selected article/34

The military of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, commanded by Crown and Lithuanian hetmans, was a successful force during the first century of the Commonwealth's existence (beginning with the Union of Lublin in 1569). Its most unique formation was the heavy cavalry in the form of the Polish winged hussars. Polish forces were engaged in numerous conflicts in the south (against the Ottoman Empire), the east (against the Russian Empire), and the north (against Sweden), as well as in internal conflicts, such as Cossack uprisings. Around the middle of the 17th century, the Commonwealth army became plagued by insufficient funds and found itself increasingly hard-pressed to defend the country from the growing armies of its neighbors. The Commonwealth Navy, on the other hand, never played a major role in the military structure, and ceased to exist in the 17th century. (Full article...)Selected article 35

Portal:Poland/Selected article/35

The Battle of Bautzen was one of the last battles on the Eastern Front of World War II. It took place on the extreme southern flank of the Spremberg-Torgau Offensive, seeing days of pitched street fighting between forces of the Polish Second Army together with elements of the Soviet 52nd Army and 5th Guards Army on one side and remnants of the German 4th Panzer and 17th Armies on the other. Part of Marshal Ivan Konev's 1st Ukrainian Front push toward Berlin, the battle was fought in the town of Bautzen and its environs along the Bautzen–Niesky line. Major combat took place from 21 to 26 April 1945, but isolated engagements continued until 30 April. The Polish Second Army under General Karol Świerczewski suffered heavy losses, but with the aid of Soviet reinforcements prevented the German forces from breaking through to their rear. According to one historian, the Battle of Bautzen was one of the Polish Army's bloodiest. Both sides claimed victory and modern views as to who won the battle remain contradictory. After the fall of communism, Polish historians became critical of Świerczewski's command, blaming the near destruction of the Polish force on his incompetence and desire to capture Dresden. (Full article...)Selected article 36

Portal:Poland/Selected article/36

The General Diet or Sejm (sejm walny) was the parliament of Poland from the 15th until the late 18th century. It was one of the primary elements of the democratic government of the Kingdom of Poland and, later, the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. From the early 16th century, Polish kings could not pass laws without the Sejm's approval. Duration and frequency of Sejm sessions changed over time, with six-week sessions convened every two years being most common. Locations changed too, but eventually Warsaw emerged as the primary venue. The number of senators and deputies (members) grew over time, from about 70 senators and 50 deputies in the 15th century to about 150 senators and 200 deputies in the 18th. Early diets used majority voting, but beginning in the 17th century, unanimous voting became more common, with the liberum veto procedure significantly paralyzing the country's governance. It is estimated that between 1493 and 1793, 240 general diets were held. (Full article...)Selected article 37

Portal:Poland/Selected article/37

The Great Sejm, or Four-Year Sejm, was a sejm (diet or parliament) of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth that was held in Warsaw between 1788 and 1792. Its principal aim became to reform and restore sovereignty to the Commonwealth. The Great Sejm's foremost achievement was the adoption of the Constitution of May 3, 1791, often described as Europe's first modern written national constitution. The constitution was designed to redress long-standing political defects of the nation and its system of Golden Liberties. It introduced political equality between townspeople and nobility and placed the peasants under the protection of the government, thus mitigating the worst abuses of serfdom. It sought to supplant the existing anarchy fostered by some of the country's reactionary magnates with a more egalitarian and democratic constitutional monarchy. The reforms instituted by the Great Sejm were undone by an intervention of the Russian Empire at the invitation of the Targowica Confederation. (Full article...)Selected article 38

Portal:Poland/Selected article/38

Selected article 39

Portal:Poland/Selected article/39

The Second Northern War was fought between 1655 and 1660 by Sweden against the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, Russia, Brandenburg-Prussia, the Habsburg Monarchy, and Denmark–Norway. In 1655, Charles X Gustav of Sweden invaded and occupied western Poland, the eastern part of which was already in Russian hands. The rapid Swedish advance became known in Poland as the Swedish Deluge. The Grand Duchy of Lithuania became a Swedish fief, Polish-Lithuanian regular armies surrendered, and King John Casimir of Poland fled to Silesia. Charles Gustav found allies in Frederick William of Brandenburg, whom he granted full sovereignty in the Polish fief of Ducal Prussia, and in George II of Transylvania, whom he promised the Polish throne. With the help of Polish Catholic guerillas of the Tyszowce Confederation, as well as Leopold I Habsburg, and Frederick William, who changed sides in return for the Polish recognition of his claim to Prussia, John Casimir was able to regain ground in 1656 and by the following year much of the fighting had moved to the Danish theater. Polish losses from the Swedish occupation, including a 40-percent drop in population, complete destruction of Warsaw and scores of other Polish towns, as well as plunder of the nation's riches and cultural artefacts, remained unmatched until World War II. (Full article...)Selected article 40

Portal:Poland/Selected article/40

The Polish–Russian War of 1792 was fought between the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth and the Russian Empire, which ostensibly came to the aid of the Targowica Confederation, a group of conservative Polish nobles opposed to the Constitution of 3 May 1791. The war took place in two theaters: northern, in Lithuania, and southern, in Ukraine. In both, the Polish forces retreated before the numerically superior Russian forces, though they offered significantly more resistance in the south, thanks to the effective leadership of Polish commanders – Prince Józef Poniatowski and General Tadeusz Kościuszko. During the three-month-long struggle several battles were fought, but neither side scored a decisive victory. The largest success of the Polish forces was the defeat of one of the Russian formations at the Battle of Zieleńce on 18 June. The Order of Virtuti Militari ("For Military Valour"), Poland's highest military award to this day, was established to celebrate this victory. The war ended when King Stanislaus Augustus of Poland, seeking a diplomatic solution, asked for a ceasefire with the Russians and joined the Targowica Confederation, as demanded by Russia. The war resulted in the abrogation of the constitution and in the Second Partition of Poland. (Full article...)Selected article 41

Portal:Poland/Selected article/41

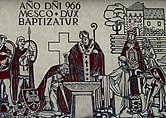

The term "baptism of Poland" traditionally refers to the personal baptism of Duke Mieszko I of Poland. The ceremony took place on the Holy Saturday of 14 April 966; the exact location is disputed by historians, with the cities of Poznań and Gniezno being the most likely sites. It was followed by Mieszko's marriage to the Bohemian princess Doubravka. The event began the process of Poland's Christianization in the Latin rite, which took centuries to complete, but helped establish Poland as a state recognized by the papacy and the Holy Roman Empire within decades. Before Mieszko's baptism, the tribes living in what is now Poland professed Slavic paganism. Their first contact with Christian faith came in the 9th century from Great Moravia in the south, where Byzantine-Slavic rite Christianity had been spread by Cyril and Methodius, but Mieszko's choice about a century later put Poland firmly within the realm of Western Christianity. In 1966, the Catholic Church in Poland and the country's Communist authorities held rival millennial celebrations to commemorate the one thousand years of, respectively, Polish Christianity and Polish nationhood. (Full article...)Selected article 42

Portal:Poland/Selected article/42

Borscht (barszcz) is a sour soup common to various Eastern European cuisines. It derives from a soup originally made by the Slavs from common hogweed, a herbaceous plant growing in damp meadows, which lent the dish its Slavic name. Its stems, leaves and umbels were chopped, covered with water and left in a warm place to ferment. After a few days, lactic and alcoholic fermentation produced a mixture described as "something between beer and sauerkraut". It was then used for cooking a soup with a mouth-puckering sour taste and pungent smell. As the Polish ethnographer Łukasz Gołębiowski wrote in 1830, "Poles have been always partial to tart dishes, which are somewhat peculiar to their homeland and vital to their health." With time, other ingredients were added to the soup, eventually replacing hogweed altogether. In modern Polish cuisine, borscht usually comes in one of two varieties: clear beetroot-based red borscht, typically served with mushroom-filled uszka dumplings (pictured), or white borscht made from fermented rye flour and served over boiled sausage, potatoes and eggs. They are traditionally associated with Christmas and Easter, respectively. (Full article...)