Back Паўхатан Byelorussian Конфедерация Поухатан Bulgarian Powhatan (grup humà) Catalan Powhatan Danish Powhatan German Paŭhatanoj Esperanto Powhatan Spanish Powhatan Basque Powhatanit Finnish Powhatans French

This article's lead section may be too long. (April 2024) |

| Regions with significant populations | |

|---|---|

| Eastern Virginia | |

| Languages | |

| Historically Powhatan, currently English | |

| Religion | |

| Indigenous religion, Christianity | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Pamlico, Nanticoke, Lenape, Massachusett, and other Algonquian peoples |

The Powhatan people (/ˌpaʊhəˈtæn, ˈhætən/[1]) are Indigenous peoples of the Northeastern Woodlands who belong to member tribes of the Powhatan Confederacy, or Tsenacommacah. They are Algonquian peoples whose historic territories were in eastern Virginia.[2]

Their Powhatan language is an Eastern Algonquian language, also known as Virginia Algonquian. In 1607, an estimated 14,000 to 21,000 Powhatan people lived in eastern Virginia when English colonists established Jamestown.[3]

The term Powhatan is also a title among the Powhatan people. English colonial historians often used this meaning of the term.[4]

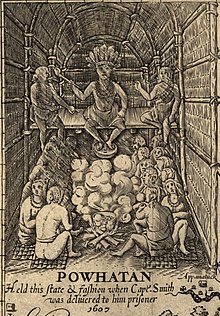

In the late 16th and early 17th centuries, a mamanatowick (paramount chief) named Wahunsenacawh forged a Paramount Chiefdom consisting of 30 tributary tribes through inheritance, marriage and war, whose territory included much of eastern Virginia. Their territory was called Tsenacommacah ("densely inhabited Land"). English colonists called Wahunsenacawh The Powhatan.[5][6] Each of the tribes within the confederacy was led by a weroance (leader, commander), all of whom paid tribute to the Powhatan.[4]

After Wahunsenacawh died in 1618, hostilities with colonists escalated under the chiefdom of his brother, Opchanacanough, who unsuccessfully tried to repel encroaching English colonists.[7] His 1622 and 1644 attacks against the invaders failed, and the English almost eliminated the confederacy. By 1646, the Powhatan Paramount Chiefdom had been decimated, not just by warfare but from the infectious diseases, such as measles and smallpox newly introduced to North America by Europeans. The Native Americans did not have any immunity to these, which had been endemic to Europe and Asia for centuries. At least 75 percent of the Powhatan people died from these diseases in the 17th century alone.[8]

By the mid-17th century, English colonist were desperate for labor to develop the land. Almost half of the European immigrants to Virginia arrived as indentured servants. As settlement continued, the colonists imported growing numbers of enslaved Africans for labor. By 1700, the colonies had about 6,000 enslaved Africans, one-twelfth of the population. Enslaved people would at times escape and join the surrounding Powhatan. Some white indentured servants were also known to have fled and joined the Indigenous peoples. African slaves and indentured European servants often worked and lived together, and while marriage was not always legal, some Native people lived, worked, and had children with them. After Bacon's Rebellion in 1676, the colony enslaved Indians for control. In 1691, the House of Burgesses abolished the enslavement of Native peoples; however, many Powhatans were held in servitude well into the 18th century.[9]

English and Powhatan people often married, with the best-known being Pocahontas and John Rolfe. Their son was Thomas Rolfe, who has more than an estimated 100,000 descendants today.[10] Many of the First Families of Virginia have both English and Virginia Algonquian ancestry.[2]

Virginia state-recognized eight Native tribes with ancestral ties to the Powhatan Confederation.[11] The Pamunkey and Mattaponi are the only two peoples who have retained reservation lands from the 17th century.[4]

Today many descendants of the Powhatan Confederacy are enrolled in six federally recognized tribes in Virginia.[12] They are:

- Chickahominy Indian Tribe

- Chickahominy Indian Tribe–Eastern Division

- Nansemond Indian Nation

- Pamunkey Indian Tribe

- Rappahannock Tribe, Inc.

- Upper Mattaponi Tribe.[12]

- ^ "Powhatan". Collins English Dictionary.

- ^ a b Cite error: The named reference

indians.vipnet.orgwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Keith Egloff and Deborah Woodward. First People: The Early Indians of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA: University Press of Virginia, 1992

- ^ a b c Sandra F. Waugaman and Danielle Moretti-Langholtz. We're Still Here: Contemporary Virginia Indians Tell Their Stories. Richmond: Palari Publishing, 2006 (revised edition).

- ^ Wood, Karenne. The Virginia Indian Heritage Trail, 2007.

- ^ Capossela, Julie Ann (February 2, 2006). "Jamestown from a Non-Western Perspective". NIAHD Journals. National Institute of American History & Democracy. Archived from the original on October 22, 2008.

- ^ Horn, James (November 16, 2021). A Brave and Cunning Prince: The Great Chief Opechancanough and the War for America. Basic Books. ISBN 978-1-5416-0003-4.

- ^ "1700: Virginia Native peoples succumb to smallpox". Native Voices. National Library of Medicine. Retrieved December 23, 2023.

- ^ Rountree 1990

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

gruenkewas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ "Matchut". www.virginiaplaces.org. Retrieved November 15, 2018.

- ^ a b Hilleary, Cecily (January 31, 2018). "US Recognizes 6 Virginia Native American Tribes". Voice of America. Retrieved December 23, 2023.