Back رئاسة وودرو ويلسون Arabic Kabinett Wilson German Présidence de Woodrow Wilson French הקבינט של ארצות הברית בממשל וודרו וילסון HE Presidenza di Woodrow Wilson Italian Kabinet-Woodrow Wilson Dutch

| |

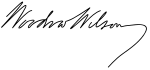

| Presidency of Woodrow Wilson March 4, 1913 – March 4, 1921 | |

| Cabinet | See list |

|---|---|

| Party | Democratic |

| Election | |

| Seat | White House |

|

| |

| Library website | |

Woodrow Wilson's tenure as the 28th president of the United States lasted from March 4, 1913, until March 4, 1921. He was largely incapacitated the last year and a half. He became president after winning the 1912 election. Wilson was a Democrat who previously served as governor of New Jersey. He gained a large majority in the electoral vote and a 42% plurality of the popular vote in a four-candidate field. Wilson was re-elected in 1916 by a narrow margin. Despite his New Jersey base, most Southern leaders worked with him as a fellow Southerner. He was succeeded by Republican Warren Harding, who won the 1920 election.

Wilson was a leading force in the Progressive Movement. During his first term, he oversaw the passage of progressive legislative policies unparalleled until the New Deal in the 1930s. Taking office one month after the ratification of the 16th Amendment of the Constitution permitted a federal income tax, he helped pass the Revenue Act of 1913, which introduced a low federal income tax to replace revenue lost in lower tariff rates. The income tax soared to high rates after the U.S. entered the world war in 1917. Other major progressive legislation passed during Wilson's first term included the Federal Reserve Act, the Federal Trade Commission Act of 1914, the Clayton Antitrust Act, and the Federal Farm Loan Act. With the passing of the Adamson Act—which imposed an 8-hour workday for railroads—he averted a threatened railroad strike. Concerning race issues, Wilson's administration reinforced segregationist policies for government agencies. He became deeply involved with a moralistic policy in dealing with Mexico's civil war. Upon the outbreak of World War I in 1914, Wilson maintained a policy of neutrality, and sought to broker a peace agreement between the belligerents.

Wilson's second term was dominated by America's roles fighting and financing the World War, and designing a postwar peaceful world. In April 1917, when Germany resumed unrestricted submarine warfare, Wilson asked Congress to declare war in order to make "the world safe for democracy." Through the Selective Service Act, conscription sent 10,000 freshly trained soldiers to France per day by summer 1918. On the home front, Wilson raised income taxes, set up the War Industries Board, promoted labor union cooperation, regulated agriculture and food production through the Lever Act, and nationalized the nation's railroad system. In his 1915 State of the Union, Wilson asked Congress for what became the Espionage Act of 1917 and the Sedition Act of 1918, suppressing anti-draft activists. The crackdown was later intensified by Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer to include expulsion of non-citizen radicals during the First Red Scare of 1919–1920. Wilson infused morality into his internationalism, an ideology now referred to as "Wilsonian"—an activist foreign policy calling on the nation to promote global democracy.[1][2] In early 1918, he issued his principles for peace, the Fourteen Points, and in 1919, following the signing of an armistice with Germany, he traveled to Paris, concluding the Treaty of Versailles. Wilson embarked on a nationwide tour to campaign for the treaty, which would have included U.S. entrance into the League of Nations. He was left incapacitated by a stroke in October 1919 and the treaty failed in the Senate.

Despite his bad health and diminished mental capacity, Wilson served the remainder of his second term and hoped to get his party's nomination for a third term. In the 1920 presidential election, Republican Warren G. Harding defeated Democratic nominee James M. Cox in a landslide. Historians and political scientists rank Wilson as an above-average president, and his presidency was an important forerunner of modern American liberalism. However, Wilson has also been criticized for his racist views and actions.

- ^ Blum, John Morton (1956). Woodrow Wilson and the Politics of Morality. Boston: Little, Brown. ISBN 9780316100212.

- ^ Gamble, Richard M. (2001). "Savior Nation: Woodrow Wilson and the Gospel of Service" (PDF). Humanitas. 14 (1): 4–22. doi:10.5840/humanitas20011411.