Back Pseudepigraaf Afrikaans كتاب منحول Arabic Pseudoepígraf Catalan Pseudepigraf Czech Ffugysgrifeniadau Welsh Pseudepigraphie German Pseŭdoepigrafio Esperanto Seudoepigrafía Spanish دروغنامیدهها Persian Pseudepigrafit Finnish

This article needs additional citations for verification. (July 2018) |

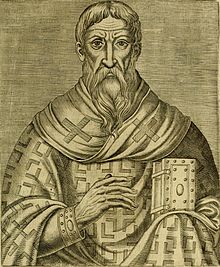

Pseudepigrapha (also anglicized as "pseudepigraph" or "pseudepigraphs") are falsely attributed works, texts whose claimed author is not the true author, or a work whose real author attributed it to a figure of the past. The name of the author to whom the work is falsely attributed is often prefixed with the particle "pseudo-",[1] such as for example "pseudo-Aristotle" or "pseudo-Dionysius": these terms refer to the anonymous authors of works falsely attributed to Aristotle and Dionysius the Areopagite, respectively.

In biblical studies, the term pseudepigrapha can refer to an assorted collection of Jewish religious works thought to be written c. 300 BCE to 300 CE. They are distinguished by Protestants from the deuterocanonical books (Catholic and Orthodox) or Apocrypha (Protestant), the books that appear in extant copies of the Septuagint in the fourth century or later[2] and the Vulgate, but not in the Hebrew Bible or in Protestant Bibles.[3] The Catholic Church distinguishes only between the deuterocanonical and all other books; the latter are called biblical apocrypha, which in Catholic usage includes the pseudepigrapha.[citation needed] In addition, two books considered canonical in the Orthodox Tewahedo churches, the Book of Enoch and Book of Jubilees, are categorized as pseudepigrapha from the point of view of Chalcedonian Christianity.[citation needed]

In addition to the sets of generally agreed to be non-canonical works, scholars will also apply the term to canonical works who make a direct claim of authorship, yet this authorship is doubted. For example, the Book of Daniel is considered by some to have been written in the 2nd century BCE, 400 years after the prophet Daniel lived, and thus the work is pseudepigraphic.[4][5] A New Testament example might be the book of 2 Peter, considered by some to be written approximately 80 years after Saint Peter's death. Early Christians, such as Origen, harbored doubts as to the authenticity of the book's authorship.[6]

The term has also been used by some Muslims to describe hadiths; who claim that most hadiths are fabrications[7] created in the 8th and 9th century CE, and falsely attributed to the Islamic prophet Muhammad (see Quranism).[8]

- ^ Bauckham, Richard (September 1988). "Pseudo-Apostolic Letters". Journal of Biblical Literature. 107 (3): 469–494. doi:10.2307/3267581. JSTOR 3267581.

- ^ Beckwith, Roger T. (2008). The Canon of the Old Testament (PDF). Eugene, OR: Wipf & Stock. pp. 62, 382–83. ISBN 978-1606082492. Retrieved 23 November 2015.

- ^ Harris, Stephen L. (2010). Understanding The Bible. McGraw-Hill Education. ISBN 978-0-07-340744-9.

- ^ Collins, John J. (1992). "Daniel, Book of". In Freedman, David Noel (ed.). The Anchor Bible dictionary. Vol. 2. New York London Toronto [etc.]: Doubleday. p. 30. ISBN 0-385-19360-2.

- ^ Ryken, Leland; Wilhoit, Jim; Longman, Tremper (1998). Dictionary of Biblical Imagery. InterVarsity Press. p. unpaginated. ISBN 9780830867332.

The consensus of modern biblical scholarship is that the book was composed in the second century B.C., that it is a pseudonymous work, and that it is indeed an example of prophecy after the fact.

- ^ Ehrman, Bart D. (2012). Forgery and Counterforgery: The Use of Literary Deceit in Early Christian Polemics. Oxford University Press. pp. 83–88. ISBN 9780199928033.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

:0was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Musa, Aisha Y. (2010). "The Qur'anists". Religious Compass. 4 (1): 12–21. doi:10.1111/j.1749-8171.2009.00189.x.