Back Publiekesleutelkriptografie Afrikaans تعمية بمفتاح عام Arabic Асиметричен шифър Bulgarian সর্বজনীন-চাবি ক্রিপ্টোগ্রাফি Bengali/Bangla Criptografia de clau pública Catalan Asymetrická kryptografie Czech Asymmetrisches Kryptosystem German Κρυπτογράφηση δημόσιου κλειδιού Greek Criptografía asimétrica Spanish Avaliku võtmega krüptograafia Estonian

This article needs additional citations for verification. (January 2024) |

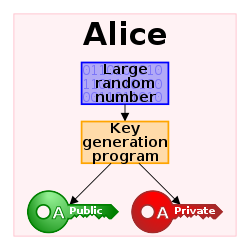

Public-key cryptography, or asymmetric cryptography, is the field of cryptographic systems that use pairs of related keys. Each key pair consists of a public key and a corresponding private key.[1][2] Key pairs are generated with cryptographic algorithms based on mathematical problems termed one-way functions. Security of public-key cryptography depends on keeping the private key secret; the public key can be openly distributed without compromising security.[3]

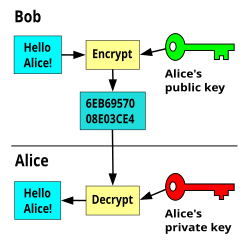

In a public-key encryption system, anyone with a public key can encrypt a message, yielding a ciphertext, but only those who know the corresponding private key can decrypt the ciphertext to obtain the original message.[4]

For example, a journalist can publish the public key of an encryption key pair on a web site so that sources can send secret messages to the news organization in ciphertext. Only the journalist who knows the corresponding private key can decrypt the ciphertexts to obtain the sources' messages—an eavesdropper reading email on its way to the journalist cannot decrypt the ciphertexts.

In a digital signature system, a sender can use a private key together with a message to create a signature. Anyone with the corresponding public key can verify whether the signature matches the message, but a forger who does not know the private key cannot find any message/signature pair that will pass verification with the public key.[5][6]

For example, a software publisher can create a signature key pair and include the public key in software installed on computers. Later, the publisher can distribute an update to the software signed using the private key, and any computer receiving an update can confirm it is genuine by verifying the signature using the public key. As long as the software publisher keeps the private key secret, even if a forger can distribute malicious updates to computers, they cannot convince the computers that any malicious updates are genuine.

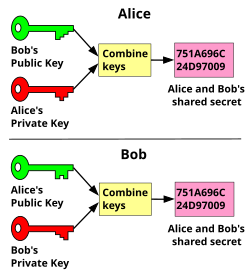

Public key algorithms are fundamental security primitives in modern cryptosystems, including applications and protocols that offer assurance of the confidentiality, authenticity and non-repudiability of electronic communications and data storage. They underpin numerous Internet standards, such as Transport Layer Security (TLS), SSH, S/MIME and PGP. Some public key algorithms provide key distribution and secrecy (e.g., Diffie–Hellman key exchange), some provide digital signatures (e.g., Digital Signature Algorithm), and some provide both (e.g., RSA). Compared to symmetric encryption, asymmetric encryption can be too slow for many purposes.[7] Today's cryptosystems (such as TLS, Secure Shell) use both symmetric encryption and asymmetric encryption, often by using asymmetric encryption to securely exchange a secret key, which is then used for symmetric encryption.

- ^ R. Shirey (August 2007). Internet Security Glossary, Version 2. Network Working Group. doi:10.17487/RFC4949. RFC 4949. Informational.

- ^ Bernstein, Daniel J.; Lange, Tanja (14 September 2017). "Post-quantum cryptography". Nature. 549 (7671): 188–194. Bibcode:2017Natur.549..188B. doi:10.1038/nature23461. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 28905891. S2CID 4446249.

- ^ Stallings, William (3 May 1990). Cryptography and Network Security: Principles and Practice. Prentice Hall. p. 165. ISBN 9780138690175.

- ^ Menezes, Alfred J.; van Oorschot, Paul C.; Vanstone, Scott A. (October 1996). "8: Public-key encryption". Handbook of Applied Cryptography (PDF). CRC Press. pp. 283–319. ISBN 0-8493-8523-7. Retrieved 8 October 2022.

- ^ Menezes, Alfred J.; van Oorschot, Paul C.; Vanstone, Scott A. (October 1996). "8: Public-key encryption". Handbook of Applied Cryptography (PDF). CRC Press. pp. 425–488. ISBN 0-8493-8523-7. Retrieved 8 October 2022.

- ^ Bernstein, Daniel J. (1 May 2008). "Protecting communications against forgery". Algorithmic Number Theory (PDF). Vol. 44. MSRI Publications. §5: Public-key signatures, pp. 543–545. Retrieved 8 October 2022.

- ^ Alvarez, Rafael; Caballero-Gil, Cándido; Santonja, Juan; Zamora, Antonio (27 June 2017). "Algorithms for Lightweight Key Exchange". Sensors. 17 (7): 1517. doi:10.3390/s17071517. ISSN 1424-8220. PMC 5551094. PMID 28654006.