Back Refusenik Afrikaans رافض (الاتحاد السوفيتي) Arabic Refusenik Catalan Refusenik Czech Refusenik German Refúsenik Spanish Refuznik (URSS) French מסורב עלייה HE Refusenik Hungarian Refusenik ID

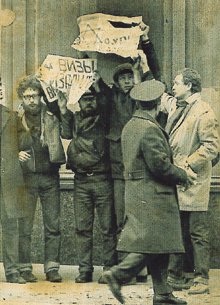

Refusenik (Russian: отказник, romanized: otkaznik, from отказ (otkaz) 'refusal'; alternatively spelled refusnik) was an unofficial term for individuals—typically, but not exclusively, Soviet Jews—who were denied permission to emigrate, primarily to Israel, by the authorities of the Soviet Union and other countries of the Soviet Bloc.[1] The term refusenik is derived from the "refusal" handed down to a prospective emigrant from the Soviet authorities.

In addition to the Jews, broader categories included:

- Other ethnicities, such as Volga Germans attempting to leave for Germany, Armenians wanting to join their diaspora, and Greeks forcibly removed by Stalin from Crimea and other southern lands to Siberia.

- Members of persecuted religious groups, such as the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church, Baptists and other Protestant groups, Jehovah's Witnesses, and Russian Mennonites.

A typical basis to deny emigration was the alleged association with Soviet state secrets. Some individuals were labelled as foreign spies or potential seditionists who purportedly wanted to abuse Israeli aliyah and Law of Return (right to return) as a means of escaping punishment for high treason or sedition from abroad.

Applying for an exit visa was a step noted by the KGB, so that future career prospects, always uncertain for Soviet Jews, could be impaired.[2] As a rule, Soviet dissidents and refuseniks were fired from their workplaces and denied employment according to their major specialty. As a result, they had to find a menial job, such as a street sweeper, or face imprisonment on charges of social parasitism.[3]

The ban on Jewish immigration to Israel was lifted in 1971, leading to the 1970s Soviet Union aliyah. The coming to power of Mikhail Gorbachev in the Soviet Union in the mid-1980s, and his policies of glasnost and perestroika, as well as a desire for better relations with the West, led to major changes, and most refuseniks were allowed to emigrate.

- ^ Mark Azbel' and Grace Pierce Forbes. Refusenik, trapped in the Soviet Union. Houghton Mifflin, 1981. ISBN 0-395-30226-9

- ^ Crump, Thomas (2013). Brezhnev and the Decline of the Soviet Union. Routledge Studies in the History of Russia and Eastern Europe. Routledge. p. 153. ISBN 978-1-134-66922-6.

- ^ "Злоупотребления законодательством о труде" Archived 2015-05-02 at the Wayback Machine, a document of the Moscow Helsinki Group.