Back Netvlies Afrikaans شبكية Arabic ܢܫܒܐ ܕܥܝܢܐ ARC Retina AST Retina Azerbaijani Сеткавіца BE-X-OLD Ретина Bulgarian অক্ষিপট Bengali/Bangla Mrežnjača BS Retina Catalan

| Retina | |

|---|---|

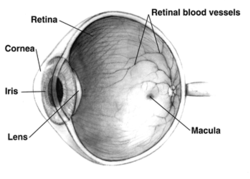

Right human eye cross-sectional view; eyes vary significantly among animals. | |

| Details | |

| Pronunciation | UK: /ˈrɛtɪnə/, US: /ˈrɛtənə/, pl. retinae /-ni/ |

| Part of | Eye |

| System | Visual system |

| Artery | Central retinal artery |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | rēte, tunica interna bulbi |

| MeSH | D012160 |

| TA98 | A15.2.04.002 |

| TA2 | 6776 |

| FMA | 58301 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

The retina (from Latin rete 'net'; pl. retinae or retinas) is the innermost, light-sensitive layer of tissue of the eye of most vertebrates and some molluscs. The optics of the eye create a focused two-dimensional image of the visual world on the retina, which then processes that image within the retina and sends nerve impulses along the optic nerve to the visual cortex to create visual perception. The retina serves a function which is in many ways analogous to that of the film or image sensor in a camera.

The neural retina consists of several layers of neurons interconnected by synapses and is supported by an outer layer of pigmented epithelial cells. The primary light-sensing cells in the retina are the photoreceptor cells, which are of two types: rods and cones. Rods function mainly in dim light and provide monochromatic vision. Cones function in well-lit conditions and are responsible for the perception of colour through the use of a range of opsins, as well as high-acuity vision used for tasks such as reading. A third type of light-sensing cell, the photosensitive ganglion cell, is important for entrainment of circadian rhythms and reflexive responses such as the pupillary light reflex.

Light striking the retina initiates a cascade of chemical and electrical events that ultimately trigger nerve impulses that are sent to various visual centres of the brain through the fibres of the optic nerve. Neural signals from the rods and cones undergo processing by other neurons, whose output takes the form of action potentials in retinal ganglion cells whose axons form the optic nerve.[1]

In vertebrate embryonic development, the retina and the optic nerve originate as outgrowths of the developing brain, specifically the embryonic diencephalon; thus, the retina is considered part of the central nervous system (CNS) and is actually brain tissue.[2][3] It is the only part of the CNS that can be visualized noninvasively. Like most of the brain, the retina is isolated from the vascular system by the blood–brain barrier. The retina is the part of the body with the greatest continuous energy demand.[4]

- ^ J, Krause William (2005). Krause's Essential Human Histology for Medical Students. Boca Raton, FL: Universal Publishers. ISBN 978-1-58112-468-2.

- ^ "Sensory Reception: Human Vision: Structure and function of the Human Eye" vol. 27, Encyclopædia Britannica, 1987

- ^ "Penn Researchers Calculate How Much the Eye Tells the Brain" (Press release). PENN Medicine. 26 July 2006. Archived from the original on 11 March 2013. Retrieved 22 April 2022.

- ^ Viegas, Filipe O.; Neuhauss, Stephan C. F. (2021). "A Metabolic Landscape for Maintaining Retina Integrity and Function". Frontiers in Molecular Neuroscience. 14. doi:10.3389/fnmol.2021.656000. ISSN 1662-5099. PMC 8081888. PMID 33935647.