Back Rochelimiet Afrikaans Buega de Roche AN حد روش Arabic Мяжа Роша Byelorussian Граница на Рош Bulgarian Rocheova granica BS Límit de Roche Catalan Rocheova mez Czech Roche-Grenze German Όριο του Ρος Greek

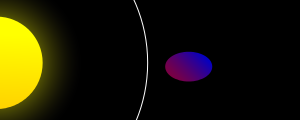

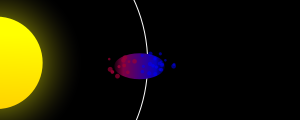

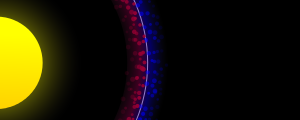

In celestial mechanics, the Roche limit, also called Roche radius, is the distance from a celestial body within which a second celestial body, held together only by its own force of gravity, will disintegrate because the first body's tidal forces exceed the second body's self-gravitation.[1] Inside the Roche limit, orbiting material disperses and forms rings, whereas outside the limit, material tends to coalesce. The Roche radius depends on the radius of the first body and on the ratio of the bodies' densities.

The term is named after Édouard Roche (French: [ʁɔʃ], English: /rɒʃ/ ROSH), the French astronomer who first calculated this theoretical limit in 1848.[2]

- ^ Weisstein, Eric W. (2007). "Eric Weisstein's World of Physics – Roche Limit". scienceworld.wolfram.com. Retrieved September 5, 2007.

- ^ NASA. "What is the Roche limit?". NASA – JPL. Archived from the original on April 23, 2009. Retrieved September 5, 2007.