Back إغراق الأسطول الفرنسي في تولون Arabic Затапленне французскага флоту ў Тулоне Byelorussian Потопяване на френския флот в Тулон Bulgarian Potopení francouzské floty v Toulonu Czech Selbstversenkung der Vichy-Flotte German Operación Lila Spanish غرق ناوگان فرانسه در تولون Persian Ranskan laivaston upottautuminen Finnish Sabordage de la flotte française à Toulon French הטבעת אוניות הצי הצרפתי בטולון HE

| Scuttling of the French fleet at Toulon | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the German occupation of Vichy France | |||||||

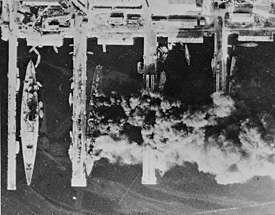

Strasbourg, Colbert, Algérie, and Marseillaise[1] | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Johannes Blaskowitz | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

164 vessels

|

| ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

77 vessels

3 destroyers (disarmed) 4 submarines (badly damaged) 39 small ships | 1 wounded[citation needed] | ||||||

The scuttling of the French fleet at Toulon was orchestrated by Vichy France on 27 November 1942 to prevent Nazi German forces from seizing it.[2] After the Allied invasion of North Africa, the Germans invaded the territory administered by Vichy under the Armistice of 1940.[3] The Vichy Secretary of the Navy, Admiral François Darlan, defected to the Allies, who were gaining increasing support from servicemen and civilians.[4] His replacement, Admiral Gabriel Auphan,[5] guessed correctly that the Germans intended to seize the large fleet at Toulon (even though this was explicitly forbidden in the Franco-Italian armistice and the French-German armistice),[6][7][8] and ordered it scuttled.[9]

The Germans began Operation Anton but the French naval crews used subterfuge to delay them until the scuttling was complete.[10] Anton was judged a failure,[11] with the capture of 39 small ships, while the French destroyed 77 vessels; several submarines escaped to French North Africa.[12] It marked the end of Vichy France as a credible naval power[13] and marked the destruction of the last political bargaining chip it had with Germany.[14][15]

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

netmarinewas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Auphan & Mordal 2016, p. 267, Chapter 22. Tragedy at Toulon and Bizerte.

- ^ Murray, Nicholas (1 June 2017). Lord, Carnes (ed.). "How the War Was Won: Air-Sea Power and Allied Victory in World War II, by Phillips PaysonO'Brien". Naval War College Review. 70 (3). Washington, D.C., United States: Naval War College: 148–149. ISSN 0028-1484. LCCN 75617787. OCLC 01779130. Retrieved 25 January 2022.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Frankwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Roberts, Priscilla (2012). "Auphan, Paul Gabriel (1894—1982)". In Tucker, Spencer C.; Pierpaoli Jr., Paul G.; Osborne, Eric W.; O'Hara, Vincent P. (eds.). World War II at Sea: An Encyclopedia. Vol. I. Santa Barbara, California, United States: ABC-CLIO. p. 66. ISBN 9781598844573 – via Google Books.

- ^ Auphan & Mordal 2016, p. 115, Chapter 12. The Misunderstanding Over Article 8.

- ^ Upward 2016, pp. 170–171, Chapter Four: Collaboration.

- ^ MacGalloway, Niall (1 February 2018). Starkey, David J.; Barnard, Michaela (eds.). "The French fleet and the Italian occupation of France, 1940–1942". International Journal of Maritime History. 30 (1). International Maritime Economic History Association/SAGE Publishing: 139–143. doi:10.1177/0843871417746892. ISSN 0843-8714. OCLC 21102214. S2CID 158144591.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

gilbertwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Black, Henry (1 April 1970). "Hopes, fears and premonitions: The French Navy, 1949-1942". Southern Quarterly. 8 (3). Hattiesburg, Mississippi, United States: University of Southern Mississippi: 309–332. ISSN 0038-4496.

- ^ Vaisset, Thomas; Vial, Philippe (1 September 2020). Viant, Julien (ed.). "Success or failure? The divided memory of the sabotage of Toulon". Inflexions. 45 (3). Paris, France: French Army/Cairn.info: 45–60. doi:10.3917/infle.045.0045. ISSN 1772-3760. S2CID 226424361.

- ^ Symonds 2018, p. 363, 16. The Tipping Point.

- ^ Clayton, Anthony (1 November 1992). Marsden, Gordon (ed.). "A Question of Honour? Scuttling Vichy's Fleet". History Today. 42 (11). London, England, United Kingdom: History Today Ltd: 32. ISSN 0018-2753.

- ^ Jackson, Peter; Kitson, Simon (2020) [2007]. "4. The paradoxes of Vichy foreign policy, 1940-1942". In Adelman, Jonathan R. (ed.). Hitler and his Allies in World War II (2 ed.). London, England, United Kingdom: Routledge. p. 82. doi:10.4324/9780203089552-4. ISBN 9780429603891. S2CID 216530750 – via Google Books.

- ^ Folly, Martin H. (2004). "The War in North Africa 1942". The Palgrave Concise Historical Atlas of the Second World War. Palgrave Concise Historical Atlases. New York City, New York, United States: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 45–46. doi:10.1057/9780230502390_23. ISBN 978-1-4039-0285-6.