Back علاقات الصين والإمبراطورية الرومانية Arabic Старажытныя кантакты паміж Кітаем і Міжземнамор’ем Byelorussian Отношения между Китай и Римската империя Bulgarian Relacions entre l'Imperi Romà i la Xina Catalan Römisch-chinesische Beziehungen German Rilatoj inter Romia Imperio kaj Ĉinujo Esperanto Relaciones Imperio romano-China Spanish روابط چین و روم باستان Persian Rooman ja Kiinan väliset yhteydet Finnish Relations entre l'Empire romain et la Chine French

c. 1st century BCE – 1453

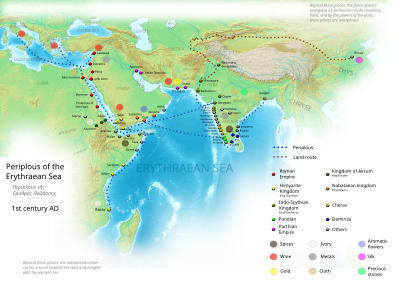

Sino-Roman relations comprised the (primarily indirect) contacts and flows of trade goods, information, and occasional travelers between the Roman Empire and the Han dynasty, as well as between the later Eastern Roman Empire and various successive Chinese dynasties that followed. These empires inched progressively closer to each other in the course of the Roman expansion into ancient Western Asia and of the simultaneous Han military incursions into Central Asia. Mutual awareness remained low, and firm knowledge about each other was limited. Surviving records document only a few attempts at direct contact. Intermediate empires such as the Parthians and Kushans, seeking to maintain control over the lucrative silk trade, inhibited direct contact between the two ancient Eurasian powers. In 97 AD, the Chinese general Ban Chao tried to send his envoy Gan Ying to Rome, but Parthians dissuaded Gan from venturing beyond the Persian Gulf. Ancient Chinese historians recorded several alleged Roman emissaries to China. The first one on record, supposedly either from the Roman emperor Antoninus Pius or from his adopted son Marcus Aurelius, arrived in 166 AD. Others are recorded as arriving in 226 and 284 AD, followed by a long hiatus until the first recorded Byzantine embassy in 643 AD.

The indirect exchange of goods on land along the Silk Road and sea routes involved (for example) Chinese silk, Roman glassware and high-quality cloth. Roman coins minted from the 1st century AD onwards have been found in China, as well as a coin of Maximian (Roman emperor from 286 to 305 AD) and medallions from the reigns of Antoninus Pius (r. 138–161 AD) and Marcus Aurelius (r. 161–180 AD) in Jiaozhi (in present-day Vietnam), the same region at which Chinese sources claim the Romans first landed. Roman glassware and silverware have been discovered at Chinese archaeological sites dated to the Han period (202 BC to 220 AD). Roman coins and glass beads have also been found in the Japanese archipelago.[1]

In classical sources, the problem of identifying references to ancient China is exacerbated by the interpretation of the Latin term Seres, whose meaning fluctuated and could refer to several Asian peoples in a wide arc from India over Central Asia to China. In the Chinese records from the Han dynasty onwards, the Roman Empire came to be known as Daqin or Great Qin. The later term Fulin (拂菻) has been identified by Friedrich Hirth and others as the Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Empire. Chinese sources describe several embassies of Fulin (Byzantine Empire) arriving in China during the Tang dynasty (618–907 AD) and also mention the siege of Constantinople by the forces of Muawiyah I in 674–678 AD.

Geographers in the Roman Empire, such as Ptolemy in the second century AD, provided a rough sketch of the eastern Indian Ocean, including the Malay Peninsula and beyond this the Gulf of Thailand and the South China Sea. Ptolemy's "Cattigara" was most likely Óc Eo, Vietnam, where Antonine-era Roman items have been found. Ancient Chinese geographers demonstrated a general knowledge of West Asia and of Rome's eastern provinces. The 7th-century AD Byzantine historian Theophylact Simocatta wrote of China's reunification under the contemporary Sui dynasty (581 to 618 AD), noting that the northern and southern halves were separate nations recently at war. This mirrors both the conquest of Chen by Emperor Wen of Sui (r. 581–604 AD) as well as the names Cathay and Mangi used by later medieval Europeans in China during the Mongol-led Yuan dynasty (1271–1368) and the Han Chinese-led Southern Song dynasty (1127–1279).