Back العبودية في الولايات المتحدة Arabic ABŞ-də köləlik Azerbaijani Esclavitud als Estats Units Catalan Slaveriet i USA Danish Sklaverei in den Vereinigten Staaten German Δουλεία στις ΗΠΑ Greek Esclavitud en los Estados Unidos Spanish بردهداری در ایالات متحده آمریکا Persian Orjuus Yhdysvalloissa Finnish Esclavage aux États-Unis French

| Part of a series on |

| Forced labor and slavery |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| African Americans |

|---|

| Part of a series on |

| Native Americans in the United States |

|---|

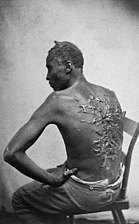

The legal institution of human chattel slavery, comprising the enslavement primarily of Africans and African Americans, was prevalent in the United States of America from its founding in 1776 until 1865, predominantly in the South. Slavery was established throughout European colonization in the Americas. From 1526, during the early colonial period, it was practiced in what became Britain's colonies, including the Thirteen Colonies that formed the United States. Under the law, an enslaved person was treated as property that could be bought, sold, or given away. Slavery lasted in about half of U.S. states until abolition in 1865, and issues concerning slavery seeped into every aspect of national politics, economics, and social custom.[1] In the decades after the end of Reconstruction in 1877, many of slavery's economic and social functions were continued through segregation, sharecropping, and convict leasing.

By the time of the American Revolutionary War (1775–1783), the status of enslaved people had been institutionalized as a racial caste associated with African ancestry.[2] During and immediately following the Revolution, abolitionist laws were passed in most Northern states and a movement developed to abolish slavery. The role of slavery under the United States Constitution (1789) was the most contentious issue during its drafting. The Three-Fifths Clause of the Constitution gave slave states disproportionate political power,[3] while the Fugitive Slave Clause (Article IV, Section 2, Clause 3) provided that, if a slave escaped to another state, the other state could not prevent the return of the slave to the person claiming to be his or her owner. All Northern states had abolished slavery to some degree by 1805, sometimes with completion at a future date, sometimes with an intermediary status of unpaid indentured servant.

Abolition was in many cases a gradual process. Some slaveowners, primarily in the Upper South, freed their slaves, and charitable groups bought and freed others. The Atlantic slave trade was outlawed by individual states beginning during the American Revolution. The import trade was banned by Congress in 1808, although smuggling was common thereafter,[4][5] at which point the U.S. Revenue Cutter Service (Coast Guard) began enforcing the law on the high seas.[6] It has been estimated that before 1820 a majority of serving congressmen owned slaves, and that about 30 percent of congressmen who were born before 1840 (some of whom served into the 20th century) at some time in their lives, were owners of slaves.[7]

The rapid expansion of the cotton industry in the Deep South after the invention of the cotton gin greatly increased demand for slave labor, and the Southern states continued as slave societies. The U.S., divided into slave and free states, became ever more polarized over the issue of slavery. Driven by labor demands from new cotton plantations in the Deep South, the Upper South sold more than a million slaves who were taken to the Deep South. The total slave population in the South eventually reached four million.[8][page needed][9] As the U.S. expanded, the Southern states attempted to extend slavery into the new Western territories to allow proslavery forces to maintain power in Congress. The new territories acquired by the Louisiana Purchase and the Mexican Cession were the subject of major political crises and compromises.[10] Slavery was defended in the South as a "positive good", and the largest religious denominations split over the slavery issue into regional organizations of the North and South.

By 1850, the newly rich, cotton-growing South threatened to secede from the Union. Bloody fighting broke out over slavery in the Kansas Territory. When Abraham Lincoln won the 1860 election on a platform of halting the expansion of slavery, slave states seceded to form the Confederacy. Shortly afterward, the Civil War began when Confederate forces attacked the U.S. Army's Fort Sumter in Charleston, South Carolina. During the war some jurisdictions abolished slavery and, due to Union measures such as the Confiscation Acts and the Emancipation Proclamation, the war effectively ended slavery in most places. After the Union victory, the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution was ratified on December 6, 1865, prohibiting "slavery [and] involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime."[11]

- ^ Abzug, Robert H. (1980). Passionate Liberator. Theodore Dwight Weld and the Dilemma of Reform. Oxford University Press. p. 87. ISBN 0-19-502771-X.

- ^ Wood, Peter (2003). "The Birth of Race-Based Slavery". Slate. (May 19, 2015): Reprinted from Strange New Land: Africans in Colonial America by Peter H. Wood with permission from Oxford University Press. 1996, 2003.

- ^ Douglass, Frederick (1849). "The Constitution and Slavery".

- ^ Smith, Julia Floyd (1973). Slavery and Plantation Growth in Antebellum Florida, 1821–1860. Gainesville: University of Florida Press. pp. 44–46. ISBN 978-0-8130-0323-8.

- ^ McDonough, Gary W. (1993). The Florida Negro. A Federal Writers' Project Legacy. University Press of Mississippi. p. 7. ISBN 978-0-87805-588-3.

- ^ Chronology of U.S. Coast Guard history on the USCG official history website.

- ^ Weil, Julie Zauzmer; Blanco, Adrian; Dominguez, Leo (January 10, 2022). "More than 1,700 congressmen once enslaved Black people. This is who they were, and how they shaped the nation". The Washington Post. Retrieved January 11, 2022.

- ^ Appiah, Anthony; Gates, Henry Louis (1999). Africana: the encyclopedia of the African and African American experience. Internet Archive. New York : Basic Civitas Books. ISBN 978-0-465-00071-5.

- ^ Introduction – Social Aspects of the Civil War Archived July 14, 2007, at the Wayback Machine, National Park Service.

- ^ "[I]n 1854, the passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act ... overturned the policy of containment [of slavery] and effectively unlocked the gates of the Western territories (including both the old Louisiana Purchase lands and the Mexican Cession) to the legal expansion of slavery...." Guelzo, Allen C., Abraham Lincoln as a Man of Ideas, Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press (2009), p. 80.

- ^ "The 13th Amendment of the U.S. Constitution". National Constitution Center – The 13th Amendment of the U.S. Constitution. Retrieved March 1, 2022.