Back مسألة سقراط Arabic Сократов проблем Bulgarian Problema socràtic Catalan Sokrata problemo Esperanto Problema socrático Spanish Arazo sokratikoa Basque مسئله سقراطی Persian Sokraattinen ongelma Finnish הבעיה הסוקרטית HE Questione socratica Italian

| Part of a series on |

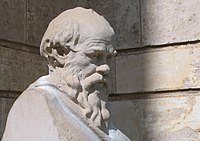

| Socrates |

|---|

|

| Eponymous concepts |

| Pupils |

| Related topics |

|

|

In historical scholarship, the Socratic problem (also called Socratic question)[1] concerns attempts at reconstructing a historical and philosophical image of Socrates based on the variable, and sometimes contradictory, nature of the existing sources on his life. Scholars rely upon extant sources, such as those of contemporaries like Aristophanes or disciples of Socrates like Plato and Xenophon, for knowing anything about Socrates. However, these sources contain contradictory details of his life, words, and beliefs when taken together. This complicates the attempts at reconstructing the beliefs and philosophical views held by the historical Socrates. It has become apparent to scholarship that this problem is seemingly impossible to clarify and thus perhaps now classified as unsolvable.[2][3] Early proposed solutions to the matter still pose significant problems today.[4]

Socrates was the main character in most of Plato's dialogues and was a genuine historical figure. It is widely understood that in later dialogues, Plato used the character Socrates to give voice to views that were his own. Besides Plato, three other important sources exist for the study of Socrates: Aristophanes, Aristotle, and Xenophon. Since no writings by Socrates himself survive to the modern era, his actual views must be discerned from the sometimes contradictory reports of these four sources. The main sources for the historical Socrates are the Sokratikoi logoi, or Socratic dialogues, which are reports of conversations apparently involving Socrates.[5] Most information is found in the works of Plato and Xenophon.[6][7]

There are also four sources extant in fragmentary states: Aeschines of Sphettus, Antisthenes, Euclid of Megara, and Phaedo of Elis.[8] In addition, there are two satirical commentaries on Socrates. One is Aristophanes's play The Clouds, which humorously attacks Socrates.[9] The other is two fragments from the Silloi by the Pyrrhonist philosopher Timon of Phlius,[10] satirizing dogmatic philosophers.

- ^ A Rubel, M Vickers, Fear and Loathing in Ancient Athens: Religion and Politics During the Peloponnesian War, Routledge, 2014, p. 147.

- ^ Prior, W. J., "The Socratic Problem" in Benson, H. H. (ed.), A Companion to Plato (Blackwell Publishing, 2006), pp. 25–35.

- ^ Louis-André Dorion (2010). "The Rise and Fall of the Socratic Problem". The Cambridge Companion to Socrates. Cambridge University Press. pp. 1–23 (The Cambridge Companion to Socrates). doi:10.1017/CCOL9780521833424.001. hdl:10795/1977. ISBN 9780511780257. Online Publication Date: March 2011 , Print Publication Year: 2010. Retrieved 2015-05-07.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Nails, Debrawas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ J Ambury. Socrates (469–399 B.C.E.) Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy [Retrieved 2015-04-19]

- ^ May, H. (2000). On Socrates. Wadsworth/Thomson Learning. p. 20.

- ^ catalogue of Harvard University Press – Xenophon Volume IV [Retrieved 2015-3-26]

- ^ CH Kahn – Plato and the Socratic Dialogue: The Philosophical Use of a Literary Form (p. 1) Cambridge University Press, 4 Jun 1998 (reprint) ISBN 0521648300 [Retrieved 2015-04-19]

- ^ Aristophanes, W.C. Green - commentary on The Clouds (p.6) Catena classicorum Rivingtons, 1868 [Retrieved 2015-04-20]

- ^ Bett, R. (11 May 2009). A Companion to Socrates. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 299–30. ISBN 978-1405192606. Retrieved 2015-04-17. (a translation of one fragment reads "But from them the sculptor, blatherer on the lawful, turned away. Spellbinder of the Greeks, who made them precise in language. Sneerer trained by rhetoricians, sub-Attic ironist." Cf. source for a discussion of this quote.