Back أبناء الحرية Arabic Azadlıq oğulları Azerbaijani Сыны свабоды (Амерыканская рэвалюцыя) Byelorussian Fills de la Llibertat Catalan Sons of Liberty German Filoj de Libereco Esperanto Hijos de la Libertad Spanish Askatasunaren Semeak Basque پسران آزادی Persian Fils de la Liberté French

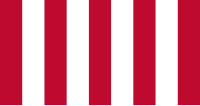

| Sons of Liberty | |

|---|---|

| |

| Leaders | See below |

| Dates of operation | 1765–1776 |

| Motives | Before 1766: Opposition to the Stamp Act After 1766: Independence of the United Colonies from Great Britain |

| Active regions | Massachusetts Bay Rhode Island New Hampshire New Jersey New York Maryland Virginia |

| Ideology | Initial phase: Rights of Englishmen "No taxation without representation" Later phase: Liberalism Republicanism |

| Major actions | Public demonstrations, direct action, destruction of Crown goods and property, boycotts, tar and feathering, pamphleteering |

| Notable attacks | Gaspee Affair, Boston Tea Party, attack on John Malcolm |

| Allies | |

| Opponents | |

The Sons of Liberty was a loosely organized, clandestine, sometimes violent, political organization active in the Thirteen American Colonies founded to advance the rights of the colonists and to fight taxation by the British government. It played a major role in most colonies in battling the Stamp Act in 1765[1] and throughout the entire period of the American Revolution. Historian David C. Rapoport called the activities of the Sons of Liberty "mob terror."[2]

In popular thought, the Sons of Liberty was a formal underground organization with recognized members and leaders. More likely, the name was an underground term for any men resisting new Crown taxes and laws.[3] The well-known label allowed organizers to make or create anonymous summons to a Liberty Tree, "Liberty Pole", or other public meeting-place. Furthermore, a unifying name helped to promote inter-Colonial efforts against Parliament and the Crown's actions. Their motto became "No taxation without representation."[4]

- ^ John Phillips Resch, ed., culture, and the homefront (MacMillan Reference Library, 2005) 1: 174–75

- ^ Rapoport, David C. (2008). "Before the Bombs There Were the Mobs: American Experiences with Terror". Terrorism and Political Violence. 20 (2): 168. doi:10.1080/09546550701856045.

- ^ Gregory Fremont-Barnes, Encyclopedia of the Age of Political Revolutions and New Ideologies (2007) 1:688

- ^ Frank Lambert (2005). James Habersham: loyalty, politics, and commerce in colonial Georgia. U. of Georgia Press. p. 173. ISBN 978-0-8203-2539-2.