Back تابير برازيلي Arabic تابير برازيلى ARZ Vaeskol (Tapirus terrestris) AVK Düzənlik tapiri Azerbaijani Бразилски тапир Bulgarian Tapir Brazil Breton Tapir amazònic Catalan Tapirus terrestris CEB Tapír jihoamerický Czech Lavlandstapir Danish

| South American tapir | |

|---|---|

| |

| Cristalino River, Brazil | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Perissodactyla |

| Family: | Tapiridae |

| Genus: | Tapirus |

| Species: | T. terrestris

|

| Binomial name | |

| Tapirus terrestris | |

| |

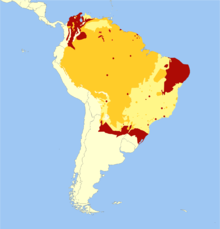

| South American tapir distribution Extinct Extant Probably extant | |

The South American tapir (Tapirus terrestris), also commonly called the Brazilian tapir (from the Tupi tapi'ira[3]), the Amazonian tapir, the maned tapir, the lowland tapir, anta (Brazilian Portuguese), and la sachavaca (literally "bushcow", in mixed Quechua and Spanish), is one of the four recognized species in the tapir family (of the order Perissodactyla, with the mountain tapir, the Malayan tapir, and the Baird's tapir).[4] It is the largest surviving native terrestrial mammal in the Amazon.[5]

Most classification taxons also include Tapirus kabomani (also known as the little black tapir or kabomani tapir) as also belonging to the species Tapirus terrestris (Brazilian tapir), despite its questionable existence and the overall lack of information on its habits and distribution. The specific epithet derives from arabo kabomani, the word for tapir in the local Paumarí language. The formal description of this tapir did not suggest a common name for the species.[6] The Karitiana people call it the little black tapir.[7] It is, purportedly, the smallest tapir species, even smaller than the mountain tapir (T. pinchaque), which had been considered the smallest. T. kabomani is allegedly also found in the Amazon rainforest, where it appears to be sympatric with the well-known South American tapir (T. terrestris). When it was described in December of 2013, T. kabomani was the first odd-toed ungulate discovered in over 100 years. However, T. kabomani has not been officially recognized by the Tapir Specialist Group as a distinct species; recent genetic evidence further suggests it is likely a subspecies of T. terrestris.[8][9]

- ^ Varela, D.; Flesher, K.; Cartes, J.L.; de Bustos, S.; Chalukian, S.; Ayala, G.; Richard-Hansen, C. (2019). "Tapirus terrestris". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2019: e.T21474A45174127. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2019-1.RLTS.T21474A45174127.en. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- ^ "Appendices | CITES". cites.org. Retrieved 2022-01-14.

- ^ Navarro, E. de A. (2013). Tupi antigo, a língua indígena clássica do Brasil. São Paulo: Global Editora e Distribuidora Ltda. p. 462

- ^ Grubb, P. (2005). "Order Perissodactyla". In Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 634. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- ^ Montenegro, Olga Lucia. The Behavior of Lowland (Tapirus terrestris) at a Natural Mineral Lick in the Peruvian Amazon. Rep. N.p.: University of Florida, 1998.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

corrwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

mongawas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Ruiz-García, Manuel; Castellanos, Armando; Bernal, Luz Agueda; Pinedo-Castro, Myreya; Kaston, Franz; Shostell, Joseph M. (2016-03-01). "Mitogenomics of the mountain tapir (Tapirus pinchaque, Tapiridae, Perissodactyla, Mammalia) in Colombia and Ecuador: Phylogeography and insights into the origin and systematics of the South American tapirs". Mammalian Biology. 81 (2): 163–175. Bibcode:2016MamBi..81..163R. doi:10.1016/j.mambio.2015.11.001. ISSN 1616-5047.

- ^ "All About the Terrific Tapir | Tapir Specialist Group". Tapir Specialist Group. Retrieved 2018-12-01.