Back Hochchinesisch ALS Ambihtlicu Cīnisc sprǣc ANG اللغة الصينية القياسية Arabic الصينيه القياسيه ARZ মান্য চীনা ভাষা Assamese Mandarín estándar AST मंदारिन भाषा AWA Standart çincə Azerbaijani Houkinäsisch BAR Стандартен мандарин Bulgarian

| Standard Chinese | |

|---|---|

| Standard Mandarin | |

| Native to | Mainland China, Taiwan, Singapore |

Native speakers | Began acquiring native speakers in 1988[1][2] L1 and L2 speakers: 80% of China[3] |

Sino-Tibetan

| |

Early forms | |

| Signed Chinese[4] | |

| Official status | |

Official language in |

|

Recognised minority language in | Malaysia |

| Regulated by | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | – |

| ISO 639-6 | |

| Glottolog | None |

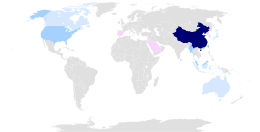

Countries where Standard Chinese is spoken

Majority native language

Statutory or de facto national working language

More than 1,000,000 L1 and L2 speakers

More than 500,000 speakers

More than 100,000 speakers | |

| Putonghua | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 普通話 | ||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 普通话 | ||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | Common speech | ||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| Guoyu | |||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 國語 | ||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 国语 | ||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | National language | ||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| Huayu | |||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 華語 | ||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 华语 | ||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | Chinese language | ||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

Standard Chinese (simplified Chinese: 现代标准汉语; traditional Chinese: 現代標準漢語; pinyin: Xiàndài biāozhǔn hànyǔ; lit. 'modern standard Han speech') is a modern standard form of Mandarin Chinese that was first codified during the republican era (1912–1949). It is designated as the official language of mainland China and a major language in the United Nations, Singapore, and Taiwan. It is largely based on the Beijing dialect. Standard Chinese is a pluricentric language with local standards in mainland China, Taiwan and Singapore that mainly differ in their lexicon.[7] Hong Kong written Chinese, used for formal written communication in Hong Kong and Macau, is a form of Standard Chinese that is read aloud with the Cantonese reading of characters.

Like other Sinitic languages, Standard Chinese is a tonal language with topic-prominent organization and subject–verb–object (SVO) word order. Compared with southern varieties, the language has fewer vowels, final consonants and tones, but more initial consonants. It is an analytic language, albeit with many compound words.

In the context of linguistics, the dialect has been labeled Standard Northern Mandarin[8][9][10] or Standard Beijing Mandarin,[11][12] and in common speech simply Mandarin,[13] more specifically qualified as Standard Mandarin, Modern Standard Mandarin, or Standard Mandarin Chinese.

- ^ Norman (1988), pp. 251.

- ^ Liang (2014), p. 45.

- ^ "Over 80 percent of Chinese population speak Mandarin", People's Daily, archived from the original on 30 September 2024, retrieved 22 December 2021

- ^ Tai, James; Tsay, Jane (2015), Sign Languages of the World: A Comparative Handbook, Walter de Gruyter, p. 772, ISBN 978-1-61451-817-4, archived from the original on 30 September 2024, retrieved 26 February 2020

- ^ Adamson, Bob; Feng, Anwei (27 December 2021), Multilingual China: National, Minority and Foreign Languages, Routledge, p. 90, ISBN 978-1-000-48702-2, archived from the original on 30 September 2024, retrieved 29 January 2024,

Despite not being defined as such in the Constitution, Putonghua enjoys de facto status of the official language in China and is legislated as the standard form of Chinese.

- ^ 國家語言發展法. law.moj.gov.tw (in Chinese). Archived from the original on 11 November 2020. Retrieved 22 May 2019.

- ^ Bradley (1992), p. 307.

- ^ Rohsenow, John S. (2004), "Fifty Years of Script and Written Language Reform in the P.R.C.", in Zhou, Minglang (ed.), Language Policy in the People's Republic of China, Springer, pp. 22, 24, ISBN 978-1-4020-8039-5,

accurately represent and express the sounds of standard Northern Mandarin (Putonghua) [...]. Central to the promotion of Putonghua as a national language with a standard pronunciation as well as to assisting literacy in the non-phonetic writing system of Chinese characters was the development of a system of phonetic symbols with which to convey the pronunciation of spoken words and written characters in standard northern Mandarin.

- ^ Ran, Yunyun; Weijer, Jeroen van de (2016), "On L2 English Intonation Patterns by Mandarin and Shanghainese Speakers: A Pilot Study", in Sloos, Marjoleine; Weijer, Jeroen van de (eds.), Proceedings of the second workshop "Chinese Accents and Accented Chinese" (2nd CAAC) 2016, at the Nordic Center, Fudan University, Shanghai, 26-27 October 2015 (PDF), p. 4, archived from the original (PDF) on 11 December 2016,

We recorded a number of English sentences spoken by speakers with Mandarin Chinese (standard northern Mandarin) as their first language and by Chinese speakers with Shanghainese as their first language, [...]

- ^ Bradley, David (2008), "Chapter 5: East and Southeast Asia", in Moseley, Christopher (ed.), Encyclopedia of the World's Endangered Languages, Routledge, p. 500 (e-book), ISBN 978-1-135-79640-2, archived from the original on 30 September 2024, retrieved 5 November 2020,

As a result of the spread of standard northern Mandarin and major regional varieties of provincial capitals since 1950, many of the smaller tuyu [土語] are disappearing by being absorbed into larger regional fangyan [方言], which of course may be a sub-variety of Mandarin or something else.

- ^ Siegel, Jeff (2003), "Chapter 8: Social Context", in Doughty, Catherine J.; Long, Michael H. (eds.), The Handbook of Second Language Acquisition, Blackwell Publishing, U.K., p. 201, ISBN 978-1-4051-5188-7, archived from the original on 30 September 2024, retrieved 5 November 2020,

Escure [Geneviève Escure, 1997] goes on to analyse second dialect texts of Putonghua (standard Beijing Mandarin Chinese) produced by speakers of other varieties of Chinese, [in] Wuhan and Suzhou.

- ^ Chen, Ying-Chuan (2013). Becoming Taiwanese: Negotiating Language, Culture and Identity (PDF) (Thesis). University of Ottawa. p. 300. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 February 2020.

[...] a consistent gender pattern found across all the age cohorts is that women were more concerned about their teachers' bad Mandarin pronunciation, and implied that it was an inferior form of Mandarin, which signified their aspiration to speak standard Beijing Mandarin, the good version of the language.

- ^ Weng, Jeffrey (2018), "What is Mandarin? The social project of language standardization in early Republican China", The Journal of Asian Studies, 59 (1): 611–633, doi:10.1017/S0021911818000487,

in common usage, 'Mandarin' or 'Mandarin Chinese' usually refers to China's standard spoken language. In fact, I would argue that this is the predominant meaning of the word

Cite error: There are <ref group=lower-alpha> tags or {{efn}} templates on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=lower-alpha}} template or {{notelist}} template (see the help page).