Back لهجة آرامية آشورية حديثة Arabic Neoarameo asiriu AST Asoru dili Azerbaijani آشور دیلی AZB Асирийски новоарамейски език Bulgarian Aturayeg Breton Assyrisk Danish Assyrisch-neuaramäischer Dialekt German Asiria lingvo Esperanto Neoarameo asirio Spanish

| Suret | |

|---|---|

| Assyrian Neo-Aramaic Chaldean Neo-Aramaic Mesopotamian Neo-Aramaic | |

| ܣܘܪܝܬ Sūret | |

Sūret written in Swāḏāyā (vernacular Eastern) Syriac | |

| Pronunciation | [ˈsuːrɪtʰ], [ˈsuːrɪθ] |

| Native to | Iran, Iraq, Syria, Turkey |

| Region | Assyrian heartland (northwestern Iran, northern Iraq, northern Syria, southern Turkey), Lebanon, Armenia,[1] global diaspora |

| Ethnicity | Assyrians |

Native speakers | 800,000 (2020)[2] |

Early forms | |

| Dialects | |

| Official status | |

Recognised minority language in | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | syr – inclusive codeIndividual codes: aii – Assyrian Neo-Aramaiccld – Chaldean Neo-Aramaic |

| Glottolog | assy1241 Assyrian Neo-Aramaicchal1275 Chaldean Neo-Aramaic |

| ELP | Aširat Northeastern Neo-Aramaic |

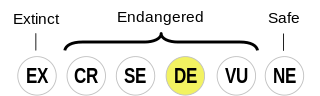

Suret is classified as Definitely Endangered by the UNESCO Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger (2010) | |

Suret (Syriac: ܣܘܪܝܬ [ˈsuːrɪtʰ] or [ˈsuːrɪθ]), also known as Assyrian,[5] refers to the varieties of Northeastern Neo-Aramaic (NENA) spoken by Christians, namely Assyrians.[6][7][8] The various NENA dialects descend from Old Aramaic, the lingua franca in the later phase of the Assyrian Empire, which slowly displaced the East Semitic Akkadian language beginning around the 10th century BC.[9][10] They have been further heavily influenced by Classical Syriac, the Middle Aramaic dialect of Edessa, after its adoption as an official liturgical language of the Syriac churches, but Suret is not a direct descendant of Classical Syriac.[11]

Suret speakers are indigenous to Upper Mesopotamia, northwestern Iran, southeastern Anatolia and the northeastern Levant, which is a large region stretching from the plain of Urmia in northwestern Iran through to the Nineveh Plains, Erbil, Kirkuk and Duhok regions in northern Iraq, together with the northerneastern regions of Syria and to southcentral and southeastern Turkey.[12] Instability throughout the Middle East over the past century has led to a worldwide diaspora of Suret speakers, with most speakers now living abroad in such places as North and South America, Australia, Europe and Russia.[13] Speakers of Suret and Turoyo (Surayt) are ethnic Assyrians and are the descendants of the ancient inhabitants of Mesopotamia.[14][15][16]

SIL distinguishes between Chaldean and Assyrian as varieties of Suret on non-linguistic grounds.[17] Suret is mutually intelligible with some NENA dialects spoken by Jews, especially in the western part of its historical extent.[18] Its mutual intelligibility with Turoyo is partial and asymmetrical, but more significant in written form.[19][20]

Suret is a moderately-inflected, fusional language with a two-gender noun system and rather flexible word order.[20] There is some Akkadian influence on the language.[21] In its native region, speakers may use Iranian, Turkic and Arabic loanwords, while diaspora communities may use loanwords borrowed from the languages of their respective countries. Suret is written from right-to-left and it uses the Madnḥāyā version of the Syriac alphabet.[22][23] Suret, alongside other modern Aramaic languages, is now considered endangered, as newer generation of Assyrians tend to not acquire the full language, mainly due to emigration and acculturation into their new resident countries.[24]

- ^ UNESCO Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger

- ^ Suret at Ethnologue (27th ed., 2024)

Assyrian Neo-Aramaic at Ethnologue (27th ed., 2024)

Chaldean Neo-Aramaic at Ethnologue (27th ed., 2024)

- ^ "Iraq's Constitution of 2005" (PDF). constituteproject.org. 1 February 2019. Retrieved 16 July 2019.

- ^ The Comprehensive Policy to Manage the Ethnic Languages in Iraq (CPMEL)

- ^ McClure, Erica (2001). "Oral and written Assyrian-English codeswitching". Codeswitching Worldwide. De Gruyter Mouton. ISBN 978-3-11-080874-2.

- ^ Talay, Shabo (2009). "Bridging the Tigris: Common features in Turoyo and North-eastern Neo-Aramaic". Suryoye l-Suryoye. Gorgias Press. pp. 161–176. doi:10.31826/9781463216603-012. ISBN 978-1-4632-1660-3.

the majority of the Christian NENA speakers belong to the Eastern Syriac Churches, who are called Assyrians and Chaldeans.

- ^ Nordhoff, Sebastian; Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2013). "Northeastern Neo-Aramaic". Glottolog 2.2. Leipzig: Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology.

- ^ Blench, 2006. The Afro-Asiatic Languages: Classification and Reference List

- ^ Beyer 1986, p. 44.

- ^ Bae, C. Aramaic as a Lingua Franca During the Persian Empire (538-333 BCE). Journal of Universal Language. March 2004, 1-20.

- ^ Fox, Samuel Ethan (1994). "The Relationships of the Eastern Neo-Aramaic Dialects". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 114 (2): 154–162. doi:10.2307/605827. ISSN 0003-0279. JSTOR 605827.

- ^ Maclean, Arthur John (1895). Grammar of the dialects of vernacular Syriac: as spoken by the Eastern Syrians of Kurdistan, north-west Persia, and the Plain of Mosul: with notices of the vernacular of the Jews of Azerbaijan and of Zakhu near Mosul. Cambridge University Press, London.

- ^ Assyrians After Assyria, Parpola

- ^ The Fihrist (Catalog): A Tench Century Survey of Islamic Culture. Abu 'l Faraj Muhammad ibn Ishaq al Nadim. Great Books of the Islamic World, Kazi Publications. Translator: Bayard Dodge.

- ^ From a lecture by J. A. Brinkman: "There is no reason to believe that there would be no racial or cultural continuity in Assyria, since there is no evidence that the population of Assyria was removed." Quoted in Efrem Yildiz's "The Assyrians" Journal of Assyrian Academic Studies, 13.1, pp. 22, ref 24

- ^ Biggs, Robert D. (2005). "My Career in Assyriology and Near Eastern Archaeology" (PDF). Journal of Assyrian Academic Studies. 19 (1): 1–23. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 February 2008. p. 10:

Especially in view of the very early establishment of Christianity in Assyria and its continuity to the present and the continuity of the population, I think there is every likelihood that ancient Assyrians are among the ancestors of modern Assyrians of the area.

- ^ Salminen, Tapani (2010). "Europe and the Caucasus". In Moseley, Christopher (ed.). Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger (3rd ed.). Paris: UNESCO Publishing. p. 41. ISBN 9789231040962.

. . . Suret (divided by SIL on non-linguistic grounds into Assyrian Neo-Aramaic and Chaldean Neo-Aramaic) . . .

- ^ Kim, Ronald (2008). ""Stammbaum" or Continuum? The Subgrouping of Modern Aramaic Dialects Reconsidered". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 128 (3): 525. ISSN 0003-0279. JSTOR 25608409.

- ^ Tezel, Aziz (2003). Comparative Etymological Studies in the Western Neo-Syriac (Ṭūrōyo) Lexicon: with special reference to homonyms, related words and borrowings with cultural signification. Uppsala Universitet. ISBN 91-554-5555-7.

- ^ a b Khan 2008, pp. 6

- ^ Khan, Geoffrey (2007). Postgate, J.N. (ed.). "Aramaic, Medieval and Modern" (PDF). British School of Archaeology in Iraq (Languages of Iraq: Ancient and Modern). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press: 110. ISBN 978-0-903472-21-0.

- ^ The Nestorians and their Rituals; George Percy Badger.

- ^ A Short History of Syriac Christianity; W. Stewart McCullough.

- ^ Naby, Eden. "From Lingua Franca to Endangered Language". Assyrian International News Agency.