Back حس مرافق Arabic Sinesteziya Azerbaijani سینستئسیا AZB Синестезия Bulgarian যুগ্মবেদন Bengali/Bangla Sinestezija BS Sinestèsia Catalan سینیستیزیا CKB Synestezie Czech Synesthesia Welsh

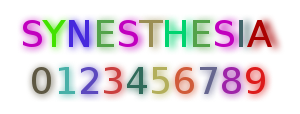

Synesthesia (American English) or synaesthesia (British English) is a perceptual phenomenon in which stimulation of one sensory or cognitive pathway leads to involuntary experiences in a second sensory or cognitive pathway.[1][2][3][4] For instance, people with synesthesia may experience colors when listening to music, see shapes when smelling certain scents, or perceive tastes when looking at words. People who report a lifelong history of such experiences are known as synesthetes. Awareness of synesthetic perceptions varies from person to person with the perception of synesthesia differing based on an individual's unique life experiences and the specific type of synesthesia that they have.[5][6] In one common form of synesthesia, known as grapheme–color synesthesia or color–graphemic synesthesia, letters or numbers are perceived as inherently colored.[7][8] In spatial-sequence, or number form synesthesia, numbers, months of the year, or days of the week elicit precise locations in space (e.g., 1980 may be "farther away" than 1990), or may appear as a three-dimensional map (clockwise or counterclockwise).[9][10] Synesthetic associations can occur in any combination and any number of senses or cognitive pathways.[11]

Little is known about how synesthesia develops. It has been suggested that synesthesia develops during childhood when children are intensively engaged with abstract concepts for the first time.[12] This hypothesis—referred to as semantic vacuum hypothesis—could explain why the most common forms of synesthesia are grapheme-color, spatial sequence, and number form. These are usually the first abstract concepts that educational systems require children to learn.

The earliest recorded case of synesthesia is attributed to the Oxford University academic and philosopher John Locke, who, in 1690, made a report about a blind man who said he experienced the color scarlet when he heard the sound of a trumpet.[13] However, there is disagreement as to whether Locke described an actual instance of synesthesia or was using a metaphor.[14] The first medical account came from German physician Georg Tobias Ludwig Sachs in 1812.[14][15][16] The term is from Ancient Greek σύν syn 'together' and αἴσθησις aisthēsis 'sensation'.[13]

- ^ Cytowic RE (2002). Synesthesia: A Union of the Senses (2nd ed.). Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-03296-4. OCLC 49395033. [page needed]

- ^ Cytowic RE (2003). The Man Who Tasted Shapes. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-53255-6. OCLC 53186027. [page needed]

- ^ Cytowic RE, Eagleman DM (2009). Wednesday is Indigo Blue: Discovering the Brain of Synesthesia (with an afterword by Dmitri Nabokov). Cambridge: MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-01279-9. [page needed]

- ^ Harrison JE, Baron-Cohen S (1996). Synaesthesia: classic and contemporary readings. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 978-0-631-19764-5. OCLC 59664610. [page needed]

- ^ Henry, Paige (19 September 2003). "Synesthesia: Definition, Explanation, And More".

- ^ van Campen C (2009). "The Hidden Sense: On Becoming Aware of Synesthesia" (PDF). Teccogs. 1: 1–13. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 July 2009.

- ^ Rich AN, Mattingley JB (January 2002). "Anomalous perception in synaesthesia: a cognitive neuroscience perspective". Nature Reviews. Neuroscience (Review). 3 (1): 43–52. doi:10.1038/nrn702. PMID 11823804. S2CID 11477960.

- ^ Hubbard EM, Ramachandran VS (November 2005). "Neurocognitive mechanisms of synesthesia". Neuron (Review). 48 (3): 509–520. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2005.10.012. PMID 16269367. S2CID 18730779.

- ^ Galton F (1880). "Visualized Numerals". Nature. 21 (543): 494–5. Bibcode:1880Natur..21..494G. doi:10.1038/021494e0. S2CID 4074444.

- ^ Seron X, Pesenti M, Noël MP, Deloche G, Cornet JA (August 1992). "Images of numbers, or "When 98 is upper left and 6 sky blue"". Cognition. 44 (1–2): 159–196. doi:10.1016/0010-0277(92)90053-K. PMID 1511585. S2CID 26687757.

- ^ "How Synesthesia Works". HowStuffWorks. 1 January 1970. Retrieved 2 May 2016.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

MroczkoNikolic2014was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b Ward, Ossian (10 June 2006). The man who heard his paint box hiss. The Telegraph. Retrieved 3 December 2018.

- ^ a b Jewanski J, Day SA, Ward J (July 2009). "A colorful albino: the first documented case of synaesthesia, by Georg Tobias Ludwig Sachs in 1812". Journal of the History of the Neurosciences. 18 (3): 293–303. doi:10.1080/09647040802431946. PMID 20183209. S2CID 8641750.

- ^ Herman LM (28 December 2018). "Synesthesia". Encyclopaedia Britannica. Retrieved 25 January 2019.

- ^ Konnikova M (26 February 2013). "From the words of an albino, a brilliant blend of color". Scientific American Blog Network. Archived from the original on 20 September 2016. Retrieved 25 January 2019.