Back Die Laaste Avondmaal (Leonardo) Afrikaans العشاء الأخير (لوحة) Arabic العشاء الاخير (لوحه) ARZ Sonuncu şam yeməyi (Leonardo da Vinçi) Azerbaijani Тайная вячэра (Леанарда да Вінчы) Byelorussian Тайната вечеря (Леонардо да Винчи) Bulgarian দ্য লাস্ট সাপার (লিওনার্দো দা ভিঞ্চি) Bengali/Bangla L'Ultima Cena (Leonardo) Breton Posljednja večera BS El Sant Sopar (Leonardo da Vinci) Catalan

| The Last Supper | |

|---|---|

| Italian: Il Cenacolo, L'Ultima Cena | |

| |

| Artist | Leonardo da Vinci |

| Year | c. 1495–1498 |

| Type | Tempera on gesso, pitch, and mastic |

| Movement | High Renaissance |

| Dimensions | 460 cm × 880 cm (181 in × 346 in) |

| Location | Santa Maria delle Grazie, Milan, Italy |

| 45°28′00″N 9°10′15″E / 45.46667°N 9.17083°E | |

| Website | cenacolovinciano |

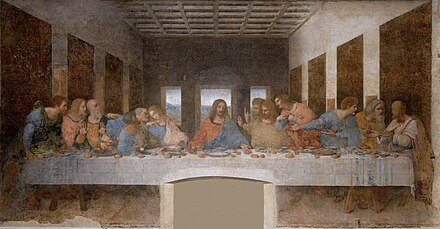

The Last Supper (Italian: Il Cenacolo [il tʃeˈnaːkolo] or L'Ultima Cena [ˈlultima ˈtʃeːna]) is a mural painting by the Italian High Renaissance artist Leonardo da Vinci, dated to c. 1495–1498, housed in the refectory of the Convent of Santa Maria delle Grazie in Milan, Italy. The painting represents the scene of the Last Supper of Jesus with the Twelve Apostles, as it is told in the Gospel of John – specifically the moment after Jesus announces that one of his apostles will betray him.[1] Its handling of space, mastery of perspective, treatment of motion and complex display of human emotion has made it one of the Western world's most recognizable paintings and among Leonardo's most celebrated works.[2] Some commentators consider it pivotal in inaugurating the transition into what is now termed the High Renaissance.[3][4]

The work was commissioned as part of a plan of renovations to the church and its convent buildings by Leonardo's patron Ludovico Sforza, Duke of Milan. In order to permit his inconsistent painting schedule and frequent revisions, it is painted with materials that allowed for regular alterations: tempera on gesso, pitch, and mastic. Due to the methods used, a variety of environmental factors, and intentional damage, little of the original painting remains today despite numerous restoration attempts, the last being completed in 1999. The Last Supper is Leonardo's largest work, aside from the Sala delle Asse.

- ^ Bianchini, Riccardo (24 March 2021). "The Last Supper by Leonardo da Vinci – Santa Maria delle Grazie – Milan". Inexhibit. Retrieved 19 October 2021.

- ^ "Leonardo Da Vinci's 'The Last Supper' reveals more secrets". sciencedaily.com. Retrieved 3 March 2014.

- ^ Frederick Hartt, A History of Art: Painting, Sculpture, Architecture; Harry N. Abrams Incorporated, New York, 1985, p. 601

- ^ Christoph Luitpold Frommel, "Bramante and the Origins of the High Renaissance" in Rethinking the High Renaissance: The Culture of the Visual Arts in Early Sixteenth-Century Rome, Jill Burke, ed. Ashgate Publishing, Oxan, UK, 2002, p. 172.