Back Trickle-down economics Czech Trickle-down-Ökonomie German Subenfiltriĝa teorio Esperanto Efecto derrame Spanish Valumaefekti Finnish Théorie du ruissellement French כלכלת חלחול HE टपकन सिद्धान्त Hindi Ekonomi menetes ke bawah ID Trickle-down Italian

| Part of a series on |

| Economics |

|---|

|

| Part of the politics series on |

| Neoliberalism |

|---|

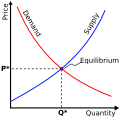

Trickle-down economics is the concept that government economic policies that disproportionately favor the upper tier of the economic spectrum (wealthy individuals and large corporations) eventually benefit the economy as a whole. The principle is founded on the idea that spending by this group "trickles down" to those less fortunate in the form of stronger economic growth.[1] The term has been used broadly by critics of supply-side economics to refer to taxing and spending policies by governments that, intentionally or not, result in widening income inequality; it has also been used in critical references to neoliberalism.[2]

Similar criticisms have existed since at least the 19th century, though the term "trickle-down economics" was popularized in the U.S. in reference to supply-side economics and the economic policies of Ronald Reagan.[3] Major examples of what critics have called "trickle-down economics" in the U.S. include the Reagan tax cuts,[4] the Bush tax cuts,[5] and the Trump tax cuts.[6] Major UK examples include Liz Truss's mini-budget tax cuts of 2022.[7] While economists who favor supply-side economics generally avoid applying the "trickle down" analogy to it and dispute the focus on tax cuts to the rich, the phrase "trickle down" has also been occasionally used by proponents of such policies.[1][8] As of 2023, studies have not shown that there is a demonstrable link between reducing tax burdens on the upper end and economic growth.[9][10][11]

- ^ a b Lockwood, Benjamin; Gomes, Joao; Smetters, Kent; Inman, Robert. "Does Trickle-down Economics Add Up – or Is It a Drop in the Bucket?". Knowledge at Wharton. A business journal from the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania. Archived from the original on February 1, 2023. Retrieved February 1, 2023.

- ^ Springer, Simon; Birch, Kean; MacLeavy, Julie (July 7, 2016). Handbook of Neoliberalism. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-54966-6.

- ^ Noah, Timothy (September 21, 2011). "New Republic: How Did Trickle-Down Get Acceptable?". National Public Radio.

- ^ Redenius, Charles (April 1983). "Thatcherism and Reagonomics: Supply-Side Economic Policy in Great Britain and the United States". Journal of Political Science. 10 (2, Article 4). The Athenaeum Press. ISSN 0098-4612. Archived from the original on December 2, 2022. Retrieved February 9, 2023.

- ^ "The Bush Tax Cuts Disproportionately Benefitted the Wealthy". Economic Policy Institute. Archived from the original on February 1, 2023. Retrieved February 1, 2023.

The Bush-era tax cuts were designed to reduce taxes for the wealthy, and the benefits of faster growth were then supposed to trickle down to the middle class.

- ^ "Trickle-down economics gets new life as Republicans push tax-cut plan". USA Today. Archived from the original on May 9, 2021. Retrieved May 7, 2021.

Behind [Republican tax legislation of 2017] is a theory long popular among conservatives: Slash taxes for corporations and rich people, who will then hire, invest and profit — and cause money to trickle into the pockets of ordinary Americans.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

lis truss favourswas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Harwood, John (November 9, 2017). "Gary Cohn: Trickle-down is good for the economy". CNBC. Retrieved January 1, 2024.

- ^ Aghion, Philippe; Bolton, Patrick (April 1997). "A Theory of Trickle-Down Growth and Development". The Review of Economic Studies. 64 (2): 151. doi:10.2307/2971707. ISSN 0034-6527. JSTOR 2971707.

- ^ Hope, David; Limberg, Julian (January 7, 2022). "The economic consequences of major tax cuts for the rich". Socio-Economic Review. 20 (2): 539–559. doi:10.1093/ser/mwab061. ISSN 1475-1461.

- ^ Arndt, H. W. (1983). "The "Trickle-down" Myth". Economic Development and Cultural Change. 32 (1): 1–10. doi:10.1086/451369. ISSN 0013-0079. JSTOR 1153421. S2CID 153842242.