Back Verenigde Koninkryk van Groot-Brittanje en Ierland Afrikaans Reino Uniu de Gran Bretanya y Irlanda AN المملكة المتحدة لبريطانيا العظمى وأيرلندا Arabic المملكه المتحده لبريطانيا العظمى و ايرلاندا ARZ Reinu Xuníu de Gran Bretaña ya Irlanda AST Böyük Britaniya və İrlandiya Birləşmiş Krallığı Azerbaijani بؤیوک بریتانیا و ایرلند بیرلشیک شاهلیغی AZB Злучанае Каралеўства Вялікабрытаніі і Ірландыі Byelorussian Обединено кралство Великобритания и Ирландия Bulgarian Rouantelezh Unanet Breizh-Veur hag Iwerzhon Breton

United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1801–1922[a] | |||||||||||||

| Motto: "Dieu et mon droit" (French) "God and my right"[1] | |||||||||||||

| Anthem:

| |||||||||||||

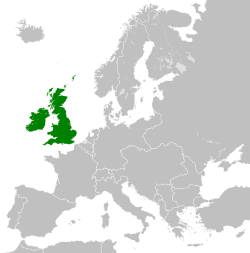

The United Kingdom in 1914 | |||||||||||||

| Capital and largest city | London 51°30′N 0°7′W / 51.500°N 0.117°W | ||||||||||||

| Official languages | English | ||||||||||||

| Demonym(s) | British | ||||||||||||

| Government | Unitary parliamentary constitutional monarchy | ||||||||||||

| Monarch | |||||||||||||

| George III | |||||||||||||

• 1820[c]–1830 | George IV | ||||||||||||

• 1830–1837 | William IV | ||||||||||||

• 1837–1901 | Victoria | ||||||||||||

• 1901–1910 | Edward VII | ||||||||||||

• 1910–1922[d] | George V | ||||||||||||

| Legislature | Parliament | ||||||||||||

| House of Lords | |||||||||||||

| House of Commons | |||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||

| 1 January 1801 | |||||||||||||

| 6 December 1921 | |||||||||||||

| 6 December 1922[a] | |||||||||||||

| Population | |||||||||||||

| 45,221,000 | |||||||||||||

| Currency |

| ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||||||

| History of the United Kingdom |

|---|

|

|

|

| History of Ireland |

|---|

|

|

|

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland was a sovereign state in Northwestern Europe that was established by the union in 1801 of the Kingdom of Great Britain and the Kingdom of Ireland.[4] The establishment of the Irish Free State in 1922 led to the remainder later being renamed the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland in 1927.

The United Kingdom, having financed the European coalition that defeated France during the Napoleonic Wars, developed a large Royal Navy that enabled the British Empire to become the foremost world power for the next century. For nearly a century from the final defeat of Napoleon following the Battle of Waterloo to the outbreak of World War I, Britain was almost continuously at peace with Great Powers. The most notable exception was the Crimean War with the Russian Empire, in which actual hostilities were relatively limited.[5] However, the United Kingdom did engage in extensive wars in Africa and Asia, such as the Opium Wars with the Qing dynasty, to extend its overseas territorial holdings and influence.

Beginning in earnest in the second half of the nineteenth century, the Imperial government granted increasing levels of autonomy to locally elected governments in colonies where white settlers had become demographically or politically dominant, with this process eventually resulting in Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Newfoundland and South Africa becoming self-governing dominions. Although these dominions remained part of the British Empire, in practice, dominion governments were permitted to largely manage their own internal affairs without interference from London, which was primarily responsible only for foreign policy.

Rapid industrialisation that began in the decades prior to the state's formation continued up until the mid-19th century. The Great Irish Famine, exacerbated by government inaction in the mid-19th century, led to demographic collapse in much of Ireland and increased calls for Irish land reform. The 19th century was an era of rapid economic modernisation and growth of industry, trade and finance, in which Britain largely dominated the world economy. Outward migration was heavy to the principal British overseas possessions and to the United States. The British Empire was expanded into most parts of Africa and much of South Asia. The Colonial Office and India Office ruled through a small number of administrators who managed the units of the empire locally, while democratic institutions began to develop. British India, by far the most important overseas possession, saw a short-lived revolt in 1857. In overseas policy, the central policy was free trade, which enabled British financiers and merchants to operate successfully in many otherwise independent countries, as in South America.

The British remained non-aligned until the early 20th century when the growing naval power of the German Empire increasingly came to be seen as an existential threat to the British Empire. In response, London began to cooperate with Japan, France and Russia, and moved closer to the United States. Although not formally allied with any of these powers, by 1914 British policy had all but committed to declaring war on Germany if the latter attacked France. This was realized in August 1914 when Germany invaded France via Belgium, whose neutrality had been guaranteed by London. The ensuing First World War eventually pitted the Allied and Associated Powers including the British Empire, France, Russia, Italy and the U.S. against the Central Powers of Germany, Austria-Hungary and the Ottoman Empire. The deadliest conflict in human history up to that point, the war ended in an Allied victory in November 1918 but inflicted a massive cost to British manpower, materiel and treasure.

Growing desire for Irish self-governance led to the Irish War of Independence almost immediately after the conclusion of World War I, which resulted in British recognition of the Irish Free State in 1922. Although the Free State was explicitly governed under dominion status and thus was not a fully independent polity, as a dominion it was no longer considered to be part of the United Kingdom and ceased to be represented in the Westminster Parliament. Six northeastern counties in Ireland, which since 1920 were being governed under a much more limited form of home rule, opted-out of joining the Free State and remained part of the Union under this limited form of self-government. In light of these changes, the British state was renamed the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland on 12 April 1927 with the Royal and Parliamentary Titles Act. The modern-day United Kingdom is the same state, that is to say a direct continuation of what remained after the Irish Free State's secession, as opposed to being an entirely new successor state.[6]

Cite error: There are <ref group=lower-alpha> tags or {{efn}} templates on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=lower-alpha}} template or {{notelist}} template (see the help page).

- ^ "The Royal Coat of Arms". The Royal Family. 15 January 2016. Archived from the original on 22 September 2020. Retrieved 19 November 2018.

- ^ "National Anthem" Archived 24 April 2020 at the Wayback Machine. Royal Family.

- ^ Fetter, Frank Whitson (3 November 2005). The Irish Pound 1797–1826: A Reprint of the Report of the Committee of 1804 of the British House of Commons on the Condition of the Irish Currency. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-4153-8211-3.

- ^ "Act of Union | United Kingdom [1801]". Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on 21 July 2017. Retrieved 1 September 2021.

- ^ Ferguson, Niall (2004). Empire, The rise and demise of the British world order and the lessons for global power. Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-4650-2328-8.

- ^ House of Commons Foreign Affairs Committee (1 May 2013). "Foreign policy considerations for the UK and Scotland in the event of Scotland becoming an independent country" (PDF). London: The Stationery Office. p. Ev 106. Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 December 2020. Retrieved 21 June 2018.