Back Urarteïes Afrikaans اللغة الأورارتية Arabic Urartuava AVK Urartu dili Azerbaijani Урарцкая мова Byelorussian Урартийски език Bulgarian Urartià Catalan Урарту чĕлхи CV Urartäische Sprache German Urarta lingvo Esperanto

| Urartian | |

|---|---|

| Vannic | |

| Native to | Urartu |

| Region | Armenian highlands |

| Era | attested 9th–6th century BCE |

Hurro-Urartian

| |

| Neo-Assyrian cuneiform | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | xur |

xur | |

| Glottolog | urar1245 |

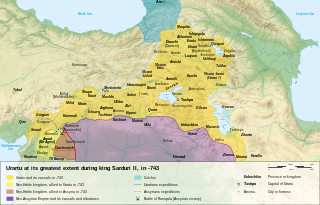

Urartu in 743 BC | |

Urartian or Vannic[1] is an extinct Hurro-Urartian language which was spoken by the inhabitants of the ancient kingdom of Urartu (Biaini or Biainili in Urartian), which was centered on the region around Lake Van and had its capital, Tushpa, near the site of the modern town of Van in the Armenian highlands, now in the Eastern Anatolia region of Turkey.[2] Its past prevalence is unknown. While some believe it was probably dominant around Lake Van and in the areas along the upper Zab valley,[3] others believe it was spoken by a relatively small population who comprised a ruling class.[4]

First attested in the 9th century BCE, Urartian ceased to be written after the fall of the Urartian state in 585 BCE and presumably became extinct due to the fall of Urartu.[5] It must have had long contact with, and been gradually totally replaced by, an early form of Armenian,[6][7][8] although it is only in the 5th century CE that the first written examples of Armenian appear.[9]

- ^ "Urartean". LINGUIST List. Archived from the original on 10 March 2021. Retrieved 5 November 2024.

- ^ Læssøe, Jørgen (1963). People of Ancient Assyria: Their Inscriptions and Correspondence. Routledge & Kegan Paul. p. 89. ISBN 9781013661396.

- ^ Wilhelm, Gernot. 2008. Urartian. In Woodard, Roger D. (ed.) The Ancient Languages of Asia Minor. P.105. "Neither its geographical origin can be conclusively determined, nor the area where Urartian was spoken by a majority of the population. It was probably dominant in the mountainous areas along the upper Zab Valley and around Lake Van."

- ^ Zimansky, Paul (1995). "Urartian Material Culture As State Assemblage: An Anomaly in the Archaeology of Empire". Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research. 299/300 (299/300): 103–115. doi:10.2307/1357348. ISSN 0003-097X. JSTOR 1357348. S2CID 164079327.

Although virtually all the cuneiform records that survive from Urartu are in one sense or another royal, they provide clues to the existence of linguistic diversity in the empire. There is no basis for the a priori assumption that a large number of people ever spoke Urartian. Urartian words are not borrowed in any numbers by neighboring peoples, and the language disappears from the written record along with the government

- ^ Wilhelm, Gernot. 2008. Urartian. In Woodard, Roger D. (ed.) The Ancient Languages of Asia Minor. P.106: "We do not know when the language became extinct, but it is likely that the collapse of what had survived of the empire until the end of the seventh or the beginning of the sixth century BCE caused the language to disappear."

- ^ Petrosyan, Armen. The Armenian Elements in the Language and Onomastics of Urartu. Aramazd: Armenian Journal of Near Eastern Studies. 2010. (https://www.academia.edu/2939663/The_Armenian_Elements_in_the_Language_and_Onomastics_of_Urartu)

- ^ Mallory, J. P.; Adams, Douglas Q., eds. (1997). Encyclopedia of Indo-European Culture. London: Fitzroy Dearborn. p. 30. ISBN 978-1884964985. OCLC 37931209.

Armenian presence in their historical seats should then be sought at some time before c 600 BC; ... Armenian phonology, for instance, appears to have been greatly affected by Urartian, which may suggest a long period of bilingualism.

- ^ Igor M. Diakonoff. The Pre-history of the Armenian People. 1968. (http://www.attalus.org/armenian/diakph11.htm)

- ^ Clackson, James P. T. 2008. Classical Armenian. In: The languages of Asia Minor (ed. R. D. Woodard). P.125. "The extralinguistic facts relevant to the prehistory of the Armenian people are also obscure. Speakers of Armenian appear to have replaced an earlier population of Urartian speakers (see Ch. 10) in the mountainous region of Eastern Anatolia. The name Armenia first occurs in the Old Persian inscriptions at Bīsotūn dated to c. 520 BCE (but note that the Armenians use the ethnonym hay [plural hayk‘] to refer to themselves). We have no record of the Armenian language before the fifth century CE. The Old Persian, Greek, and Roman sources do mention a number of prominent Armenians by name, but unfortunately the majority of these names are Iranian in origin, for example, Dādrši- (in Darius’ Bīsotūn inscription), Tigranes, and Tiridates. Other names are either Urartian (Haldita- in the Bīsotūn inscription) or obscure and unknown in literate times in Armenia (Araxa- in the Bīsotūn inscription)."