Back Giordano Bruno Afrikaans ጆርዳኖ ብሩኖ Amharic Giordano Bruno AN جوردانو برونو Arabic جيوردانو برونو ARZ Giordano Bruno AST Cordano Bruno Azerbaijani جوردانو برونو AZB Джордано Бруно Bashkir Giordano Bruno BAT-SMG

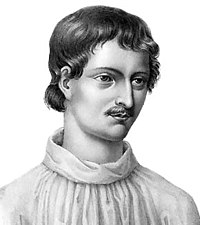

| Giordano Bruno | |

|---|---|

| Nascimento | Filippo Bruno 1548 Nola |

| Morte | 17 de fevereiro de 1600 (52 anos) Roma |

| Cidadania | Reino de Nápoles |

| Alma mater | |

| Ocupação | astrônomo, filósofo, poeta, escritor, professor universitário, astrólogo, matemático, padre católico de rito romano |

| Empregador(a) | Universidade de Helmstedt, Universidade de Oxford, Universidade de Paris, Universidade de Toulouse, San Domenico Maggiore |

| Movimento estético | humanismo renascentista, neoplatonismo, neopitagorismo |

| Religião | Igreja Católica |

| Causa da morte | morte na fogueira |

Giordano Bruno (Italiano: [dʒorˈdaːno ˈbruːno]; em latim: Iordanus Brunus Nolanus; nascido Filippo Bruno, (Nola, Reino de Nápoles, 1548[1] – Campo de' Fiori, Roma, 17 de fevereiro de 1600) foi um teólogo, filósofo, escritor, matemático, poeta, teórico de cosmologia, ocultista hermético e frade dominicano italiano[2][3][4] condenado à morte na fogueira pela Inquisição romana (Congregação da Sacra, Romana e Universal Inquisição do Santo Ofício) com a acusação de heresia[5] ao defender alegações consideradas erros teológicos. É também referido como Bruno de Nola ou Nolano.[6] É considerado por alguns como um mártir da igreja dos tempos de então, tendo contribuído para avanços significativos do conhecimento do seu tempo.[7] Ele é conhecido por suas teorias cosmológicas, que conceitualmente estenderam o então novo modelo copernicano. Ele propôs que as estrelas fossem sóis distantes cercados por seus próprios planetas e levantou a possibilidade de que esses planetas criassem vida neles próprios, uma posição filosófica conhecida como pluralismo cósmico. Ele também insistiu que o universo é infinito e não poderia ter "centro". Ele também é conhecido por ser um dos principais expoentes do Panteísmo.[8]

A partir de 1593, Bruno foi julgado por heresia pela Inquisição romana, acusado de negar várias doutrinas católicas essenciais, incluindo a condenação eterna, a Trindade, a divindade de Cristo, a virgindade de Maria e a transubstanciação. O panteísmo de Bruno também era motivo de grande preocupação,[9] assim como seus ensinamentos sobre a transmigração da alma. A Inquisição o considerou culpado e ele foi queimado na fogueira no Campo de' Fiori, em Roma, em 1600. Após sua morte, ganhou fama considerável, sendo particularmente comemorado por comentaristas do século XIX e início do século XX que o consideravam mártir de ciência,[10] embora os historiadores concordem que seu julgamento por heresia não foi uma resposta a seus pontos de vista astronômicos, mas sim uma resposta a seus pontos de vista filosóficos e religiosos.[11][12][13][14][15] Já outros historiadores consideram sim que suas visões cosmológicas foram o principal motivo ou um dos principais da condenação (heresia da pluralidade dos mundos).[16][17][18] O caso de Bruno ainda é considerado um marco na história do livre pensamento e das ciências emergentes.[19][20]

Além da cosmologia, Bruno também escreveu extensivamente sobre a arte da memória, um grupo pouco organizado de técnicas e princípios mnemônicos. A historiadora Frances Yates argumenta que Bruno foi profundamente influenciado pela astrologia árabe (particularmente a filosofia de Averróis[21]), neoplatonismo, hermetismo renascentista e lendas do gênero Gênesis em torno do deus egípcio Tote.[22] Outros estudos de Bruno se concentraram em sua abordagem qualitativa da matemática e sua aplicação dos conceitos espaciais da geometria na linguagem.[23]

- ↑ Enciclopédia Católica, Giordano Bruno

- ↑ «Quem foi Giordano Bruno?». Revista Galileu. Globo.com. Consultado em 21 de outubro de 2017

- ↑ Gatti, Hilary. Giordano Bruno and Renaissance Science: Broken Lives and Organizational Power. Cornell University Press, 2002, 1, ISBN 0-801-48785-4

- ↑ Bruno era matemático e filósofo, mas não é considerado astrônomo pela comunidade astronômica moderna, pois não há registros dele realizando observações físicas, como foi o caso de Brahe, Kepler e Galileo. Pogge, Richard W. http://www.astronomy.ohio-state.edu/~pogge/Essays/Bruno.html 1999.

- ↑ Spectator, edição de 27 de maio de 1712, p.331 [em linha]

- ↑ Bombassaro, Luiz Carlos. Giordano Bruno e a filosofia na Renascença, Caxias do Sul: Educs, 2008

- ↑ Estudos da Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian

- ↑ «Was Giordano Bruno a Heretic? A Deeper Look into His Pantheism». TheCollector (em inglês). 1 de outubro de 2022. Consultado em 16 de setembro de 2024

- ↑ Birx, James H. "Giordano Bruno" The Harbinger, Mobile, AL, 11 November 1997. "Bruno was burned to death at the stake for his pantheistic stance and cosmic perspective."

- ↑ Arturo Labriola, Giordano Bruno: Martyrs of free thought no. 1

- ↑ Frances Yates, Giordano Bruno and the Hermetic Tradition, Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1964, p. 450

- ↑ Michael J. Crowe, The Extraterrestrial Life Debate 1750–1900, Cambridge University Press, 1986, p. 10, "[Bruno's] sources... seem to have been more numerous than his followers, at least until the eighteenth- and nineteenth-century revival of interest in Bruno as a supposed 'martyr for science.' It is true that he was burned at the stake in Rome in 1600, but the church authorities guilty of this action were almost certainly more distressed at his denial of Christ's divinity and alleged diabolism than at his cosmological doctrines."

- ↑ Adam Frank (2009). The Constant Fire: Beyond the Science vs. Religion Debate, University of California Press, p. 24, "Though Bruno may have been a brilliant thinker whose work stands as a bridge between ancient and modern thought, his persecution cannot be seen solely in light of the war between science and religion."

- ↑ White, Michael (2002). The Pope and the Heretic: The True Story of Giordano Bruno, the Man who Dared to Defy the Roman Inquisition, p. 7. Perennial, New York. "This was perhaps the most dangerous notion of all... If other worlds existed with intelligent beings living there, did they too have their visitations? The idea was quite unthinkable."

- ↑ Shackelford, Joel (2009). «Myth 7 That Giordano Bruno was the first martyr of modern science». In: Numbers, Ronald L. Galileo goes to jail and other myths about science and religion. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. p. 66 "Yet the fact remains that cosmological matters, notably the plurality of worlds, were an identifiable concern all along and appear in the summary document: Bruno was repeatedly questioned on these matters, and he apparently refused to recant them at the end.14 So, Bruno probably was burned alive for resolutely maintaining a series of heresies, among which his teaching of the plurality of worlds was prominent but by no means singular."

- ↑ Gatti, Hilary (26 de outubro de 2012). «Why Giordano Bruno's "Tranquil Universal Philosophy" Finished in a Fire». In: Lavery, Jonathan; Groarke, Louis; Sweet, William. Ideas under Fire: Historical Studies of Philosophy and Science in Adversity (em inglês). [S.l.]: Fairleigh Dickinson. pp. 116–118

- ↑ Martinez, Alberto A. (outubro de 2016). «Giordano Bruno and the heresy of many worlds». Annals of Science (em inglês) (4): 345–374. ISSN 0003-3790. doi:10.1080/00033790.2016.1193627. Consultado em 8 de julho de 2023

- ↑ Koyré, Alexandre (1980). Estudios galileanos. México D.F.: Siglo XXI Editores. pp. 159–169.

- ↑ Gatti, Hilary (2002). Giordano Bruno and Renaissance Science: Broken Lives and Organizational Power. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. pp. 18–19. ISBN 978-0801487859. Consultado em 21 de março de 2014.

For Bruno was claiming for the philosopher a principle of free thought and inquiry which implied an entirely new concept of authority: that of the individual intellect in its serious and continuing pursuit of an autonomous inquiry… It is impossible to understand the issue involved and to evaluate justly the stand made by Bruno with his life without appreciating the question of free thought and liberty of expression. His insistence on placing this issue at the center of both his work and of his defense is why Bruno remains so much a figure of the modern world. If there is, as many have argued, an intrinsic link between science and liberty of inquiry, then Bruno was among those who guaranteed the future of the newly emerging sciences, as well as claiming in wider terms a general principle of free thought and expression.

- ↑ Montano, Aniello (2007). Antonio Gargano, ed. Le deposizioni davanti al tribunale dell'Inquisizione. Napoli: La Città del Sole. p. 71.

In Rome, Bruno was imprisoned for seven years and subjected to a difficult trial that analyzed, minutely, all his philosophical ideas. Bruno, who in Venice had been willing to recant some theses, become increasingly resolute and declared on 21 December 1599 that he 'did not wish to repent of having too little to repent, and in fact did not know what to repent.' Declared an unrepentant heretic and excommunicated, he was burned alive in the Campo dei Fiori in Rome on Ash Wednesday, 17 February 1600. On the stake, along with Bruno, burned the hopes of many, including philosophers and scientists of good faith like Galileo, who thought they could reconcile religious faith and scientific research, while belonging to an ecclesiastical organization declaring itself to be the custodian of absolute truth and maintaining a cultural militancy requiring continual commitment and suspicion.

- ↑ «Giordano Bruno». Encyclopædia Britannica

- ↑ A obra principal sobre o relacionamento entre Bruno e o hermetismo é Frances Yates, Giordano Bruno and The Hermetic Tradition, 1964; para uma abordagem alternativa, pondo mais ênfase na Cabala, e menos no hermetismo, ver Karen Silvia De Leon-Jones, Giordano Bruno and the Kabbalah, Yale, 1997; para uma volta à ênfase do papel de Bruno no desenvolvimento da ciência, e crítica da ênfase de Yates nos temas mágicos e herméticos, ver Hillary Gatti (1999), Giordano Bruno and Renaissance Science, Cornell.

- ↑ Alessandro G. Farinella and Carole Preston, "Giordano Bruno: Neoplatonism and the Wheel of Memory in the 'De Umbris Idearum'", in Renaissance Quarterly, Vol. 55, No. 2, (Summer, 2002), pp. 596–624; Arielle Saiber, Giordano Bruno and the Geometry of Language, Ashgate, 2005